- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

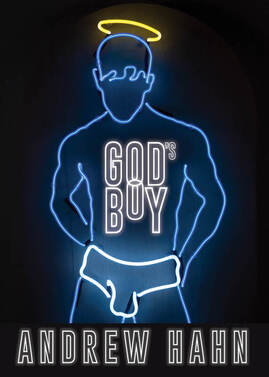

Book Review: God's Boy by Andrew Hahn

Andrew Hahn is a queer poet and writer living in Fort Lauderdale. He has his MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts and was invited to be the writer-in-residence at Randolph College. His poetry and essays can be found online at Screen Door Review, Butter Press, Crab Fat Magazine, Crab Creek Review, and Pithead Chapel among others.

|

Review

|

A Review of Andrew Hahn's God's Boy

Andrew Hahn’s God’s Boy highlights its subject’s body on the line between condemnation and pleasure, using eroticism to queer hyper-masculine Christian traditions. Hahn’s poems apply Christian ritual and worship in order to reveal different interpretations of biblical teachings to show poetry’s position in changing the perspective of dominant society’s values and beliefs. In Hahn’s titular piece, the poem begins with an informing epigraph: “liberty university is the world’s largest evangelical university.” The setting implies an intimidating authority for queer people, and yet Hahn prevails to deliver a collection of confessional poems that don’t ask for absolution. “God’s boy” narrates a forewarning from a “pastor emerick,” who heralds: “you don’t want to be a dad/dy’s boy […] / you’re God’s boy.” The speaker thinks: “dad/dies call twinks boy in the videos i love.” The repentance of “God,” “dad/dy,” and “boy” throughout the piece focuses on roles between dominant and submissive figures. Although “boy” answers to both “God” and “dad/dy,” Hahn demonstrates explicit thrill in the submissive role: “if only God knew how it felt to worship.” Supposing “boy” falls under a submissive category, the poem’s perspective of “boy” is by no means a passive role. The speaker privileges “boy’s” arousal, and absorbs the active act of language, dominating the presence of those who stand over “boy’s” body. Throughout God’s Boy, Hahn reproduces biblical characters, transforming them into familial characters to represent the relationships between the subject and God as well as the subject and his father. In “a faggot tries to be christ-like,” the piece likens God and Jesus to a father and son: w the way my father sometimes looks at me In connecting Jesus to a gay son and God to a homophobic father, the sacrificial offering centers on suffering instead of salvation, as if to erase the holiness of the biblical significance. Furthermore, Hahn reasons the social phenomenon of homophobic fathers disowning their gay sons as deriving from the crucifixion of Christ: “is this how the church creates gods from men.” Hahn’s poem reimagines the crucifixion to rationalize society’s centuries of homophobic social conditions, disclosing a reflexive analogy between history and present.

Moreover, Hahn’s God’s Boy further discusses the creation of social categorizations, investigating the semiotics of the recurring word “faggot.” Interestingly, in “boys like us,” the poem doesn’t intentionally use the word “faggot,” but represents the word through metaphor and analogy: he doesn’t know these people used to burn boys like us at the stakes The piece assumes the reader is familiar with the etymology of the word “faggot” from its beginnings to “bundles for burning” to “our name.” In discarding fear, the poem subverts the violent connotations engendered in the word, and instead accepts the “name” as such. Hahn’s poem teeters between the implicit and the explicit as the images of immolation describe the violence against queer people, while the poem speaks to true events:

when these people set us ablaze Hahn’s “boys like us” denotes the history of violence of the gay slur, while reclaiming the term to revert connotative power of language to the people who “faggot” claims to define.

Andrew Hahn’s God’s Boy worships poetic craft for its ability to confess the conflict between queerness and Christian tradition, situating language as the tool and space for reclaiming stolen power. Hahn’s explicit use of eroticism reveals an epistemology for queer people navigating marginalizing environments, using the past to subvert dominant social conditions based on gender and sexual discrimination. In “the river: schroon lake,” the speaker contemplates, “i imagined how a home can be beautiful after Hell devastates it"; and, it is the poem’s meditation the collection transgresses. God’s Boy depicts a close intimacy with violence, and yet enkindles the beauty of queer people, their survival, and their pilgrimage to a home of healing and of unrepentant love. |

|

Miguel is a Lewis University alum. He is the Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. He has been published in 30N, EFNIKS, Rogue Agent, The Rising Phoenix Review among other places. He is a fellow of the Wolny Writing Residency. He also writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog: Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >