- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

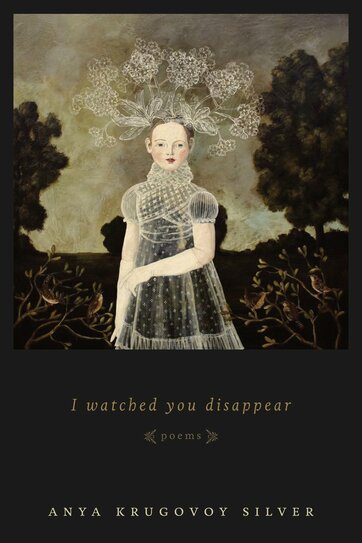

Book Review: I Watched You Disappear by Anya Krugovoy Silver

Anya Silver was the author of the poetry collections Second Bloom (2017), From Nothing (2016), I Watched You Disappear (2014), and The Ninety-Third Name of God (2010). Her book of literary criticism, Victorian Literature and the Anorexic Body, was published in 2006. She earned a BA from Haverford College and a PhD in Literature from Emory University. She was named Georgia Author of the Year for Poetry in 2015 and was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship in 2018. She taught at Mercer University and lived in Georgia until her death in 2018.

|

Review

|

A Review of Anya Krugovoy Silver's I Watched You Disappear

Who is ready to face “the evil thing,” the daemon, Dybbuk, the magician, the curse of terminal cancer? Who is prepared “to take only what [one] can carry,” enter the “wet and sucking bog?” Anya Silver’s I Watched You Disappear is a memorial, a tribute, and a testament to those who do. Her four-stage poetry collection is dedicated to women with inflammatory breast cancer—friends “who exist in stages,” with and for whom Silver embarks on a Ulyssean journey into the “coming silence,” where, as the epigraph by Tomas Tranströmer signifies, the emptiness “turns its face to us and whispers: ‘I am not empty, I am open.’” Beginning with the title of the collection, an allusion to Tom Wait’s hoarsely lyrical song, Silver’s speaker watches—oneself and others—disappear. Silver uses the multiple definitions of the “watch” throughout the collection, referring to the multi-sensual experience of disappearing, the scrutiny of death, the cyclical time-flow, and the engulfing need to protect. In the poem “Night Prayer,” the speaker’s vigil begins. The sharpened senses do not allow answers to one’s prayers, but rather a discovery of what is not there: ...not the slightest flutter of humid air The vivid images substantiate only emptiness, while the sounds of alliteration and sibilance stress only silence. The metaphors of diminutive living things—the cicadas, the swallowtail, the beetle—encapsulate the overwhelming realization the speaker confronts that “[t]he clock’s face does not waver,” our existence is finite and the words spoken into the night are nothing more than a “beetle’s breath.” “Night Prayer” is the port of departure for the collection of poems which diagnose and treat despair, anger, and “the foul smell of loss.”

Silver’s poetry takes a chemo-like approach to death, taking care to leave no cells of cancerous illusion. Despite the terror, Silver closes her eyes to nothing—not to the hospital reality of injections “into a port drilled, eye-like, into her skull,” not to “tubes dangling from our wrists, trailing behind as we walk to the bathroom,” nor to the “nighttime cries of a man withered / child-size by cancer, and the bells / of emptied IV’s tolling through hallways.” She welcomes the pain and promise of periwinkle toxin in her chemo, feels the freedom of “shaved lawn” underfoot, and welcomes the orange moth and yellow fields as she emerges back into the world that is “thick and transparent as honey.” As with chemo, acceptance and survival are the goals of Silver’s poetry. Though the truth of dying be “obscene,” it cannot be hidden by the “sweet crooning” of wishful thinking or disguised by a new dress. In “Skirts and Dresses,” the speaker recalls the pleasure of dressing the body, only to realize how little time there is to celebrate it: Because the razor of illness is at my skull. The poems grapple with the fear of changes in the declining body, struggle against that “razor” which cuts beauty and strength, and look for ways to stitch together what still remains.

Silver’s collection employs various grief-healing methods. Part II contains a series of poems based on Grimm brothers’ fairy tales. Each of these poems looks at another sorrow of sickness, from the irreversible physical transformation of the body into an owl-like creature, to the princess “locked in crystal,” trapped in a life in which she cannot participate. The poems are filled with “young, or old, / mothers, maidens,” collapsing, wailing, burning, lost; some of them reverting from monstrous to lovely, emerging from their encounters with “the evil thing” scarred but alive, nurturing, stone-willed. With an extended metaphor of a mother-poet who dies and turns into a mother-tree, whose nuts are words for her son, Part II transitions the reader into the next stage, the record of the language “sown ... in his eyes so he could dream.” Part III translates “watching” into a poetic guardianship, into lyrical stories of a shared family life. Mundane moments—like losing baby teeth—seemingly unworthy of praise, elevated through imagery, become a mindful memento that life, like a grasshopper, “leaping and skating / across the spines of stalks,” is too fast to be caught no matter how hard one “flings himself” at it. The poems in Part III project a slideshow of family photos; the speaker makes peace with all that she has known and that she has never seen. These poems refine the past through “dark places” and “deep swells,” salvage shards of beauty, and lift them up to sunlight like the “opaque and velveteen” sea glass. The theme of survival returns in a new form, equally honest but tender as one’s goodbye. The culminating stage of the collection consists of a series of ekphrastic poems, of which “Valentine Gode-Darel (1873-1915)” is especially memorable. The poem is a sequence of five vignettes based on the paintings by Ferdinand Hodler, witnessing the slow death of a beautiful woman, the painter’s wife. The poem captures the death scene first, and, by degrees, with each subsequent vignette, the woman’s vitality and beauty return, until “[h]er eyes are so heavy with love that her lids droop. / Soon, she will bear a daughter. How fruitful her body.” A woman resurrects in poetry—the cycle repeats itself within each stage, within the entire collection, and casts hope into the future for those who remain to see the miracle. What remains is the acceptance and survival, achieved collectively, says the speaker in “‘Aren’t we all so brave?’”: Because those before us have scattered bravery I Watched You Disappear, through rich illuminations, allusions, references, dedications,

and epigraphs, draws on the strength of our humanity in the Promethean effort to leave us with fire and light. |

|

Kasia Wolny is a senior at Lewis University majoring in English Literature with creative writing minor. She is the fiction, creative nonfiction, and copy editor at the Jet Fuel Review. She serves as a Vice-President of Sigma Tau Delta. International English Honor Society, Rho Lambda Chapter. She lives in the Chicago suburbs with her husband, two children, and a golden doodle pup. She and her family recently established the Wolny Writing Residency for Lewis faculty, students and alums.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >