- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

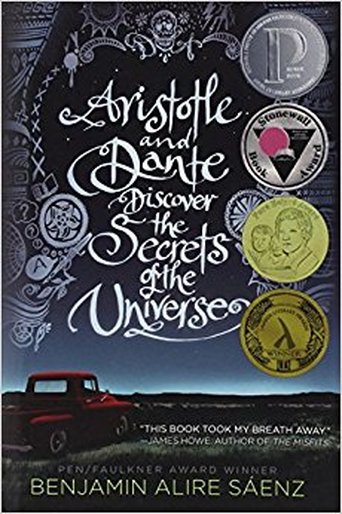

Book Review: Benjamin Alire Sáenz's Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe

Benjamin Alire Sáenz is an American novelist and poet. In 1992, he was awarded the Lannan Literary Fellowship. He is a former Wallace E. Stegner Fellow in poetry at Stanford University. His first book of poems, Calendar Dust, was awarded an American Book Award in 1991. His second collection of poems, Dark and Perfect Angels, won a Southwest Book award in 1992. Benjamin Alire Sáenz is also the author of, Elegies in Blue, his third collection of poems, and Carry Me Like Water (1995), The House of Forgetting (1997), In Perfect Light (2008), and Names on a Map (2008). His essay, “Exile,” about living in El Paso, with the increasing, overwhelming authority coming from the United States’ border control, is featured in the anthology, U.S. Latino Literature Today, which is taught in many U.S. Latino/a university courses. For Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, Benjamin Alire Sáenz is the recipient of, the Stonewall Book Award, Mike Morgan & Larry Romans Children’s and Young Adult Literature Award, Michael L. Printz Award, and Pura Belpré Award.

|

Review

|

A Review of Benjamin Alire Sáenz's Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Miguel Soto

Aristotle Mendoza, or Ari, is a Mexican-American fifteen-year-old boy, living in El Paso, Texas in 1987, who serves as our narrator. Ari has two older sisters, Cecilia and Sylvia, and one older brother, Bernardo, who is never spoken of, but we know is in prison. Much of Ari’s social interactions are done with his family—outside of interacting with Dante, the novel’s core—making one of this novel’s themes about family, which is ironic, given the way Ari’s parents repress Bernardo’s memory. His parent’s response to dealing with the loss of their son reflects how Ari deals with his own identity, especially when he expresses, “guys really made me uncomfortable. I don’t know why, not exactly. I just, I don’t know, I just didn’t belong. I think it embarrassed the hell out of me that I was a guy.” This reflection of himself adds to his later fear of “coming out,” since the outdated notion is, admitting one’s sexual fluidity makes a young man less of a man. He shapes himself into someone he thinks will please his parents “because of my brother, whose existence was not even acknowledged, I had to be a good boy scout.” The protagonists of Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe appear with odd, archaic names, but effectively provide the weight the characters deserve. Ari meets Dante at the pool house where it is Dante who approaches Ari, in a twist to the allusion it is meant to conjure. The interactions between Virgil and Dante from The Divine Comedy are replicated in Ari and Dante. The allusion to Dante and Virgil are built into the identities of their character. We learn Ari is an agnostic, from a conversation between him and Dante, to which he asks, “Do you think it’s bad—to doubt?” Ari is an amalgamation of Aristotle and Virgil, two infamous heretics, even though they were born before the revelations of Christ. Virgil takes up from Aristotle, the philosopher, and keeps the same self-reflecting questions in mind throughout The Divine Comedy, which we see uniquely molded into these teens. Dante carries the same attitude as the person he alludes, Dante Alighieri, especially when he says, “’That’s because people are lazy and undisciplined,’” which reflects how certain Dante Alighieri was in his moral-code, principally in the conversations of Christ and God. These allusions act as the identifying markers of our protagonists and reveal why Ari questions his sexuality, looking for a concrete cause to his realization, while Dante can come to terms with his sexuality. In the end, we question, who really guided whom. Nationality and heritage are present in the teens’ fluctuating identity. Ari claims Dante is a “pocho,” which is defined as “a half-assed Mexican”; and, although Ari and Dante joke around, it is a persistent, reoccurring theme. For Ari, being Mexican is easier to identify with, since his home has always been in El Paso, but for Dante, being Mexican isn’t central to his identity, which he blames on “the people who handed [him] their genes.” Dante sees culture through empirical contact zones, like Ari’s red pick-up truck, which reinforces the notion, “real chrome rims…You’re a real Mexican.” Except, the point Ari makes is, “So are you.” Benjamin Alire Sáenz is giving a platform for new narratives within the Mexican-American community. Culture and heritage intersect with sexuality, when Dante asks, “Do real Mexicans like to kiss boys,” and Ari answers, “I don’t think liking boys is an American invention.” The teens are learning to cope with a new subculture full of intersections that are not supported by either group: Anglo heteronormative or Mexican heteronormative. This is a punctuating point in the novel because the teens are creating new terrains within the hetero Anglo-dominant culture while preserving their parent’s Mexican heritage, all while coming to terms with their sexuality. Ari’s mother, not aware of Ari’s sexuality, presents an analogy to define the intersections the teens are experiencing: “In an ecotone, the landscape will contain elements of the two different ecosystems. It’s like a natural borderlands.” The teens live in the “borderlands;” they are already living in two worlds they must constantly cross, and their coming to knowledge of their sexuality only creates another border, which the two share. Benjamin Alire Sáenz’s extended metaphor is universal and alluring, with the way the teens share the symbolism of Dante’s tennis shoes. In the beginning of the boys’ friendship, Dante makes a game of throwing his tennis shoes across the street because he hates being forced to wear them. He grabs his tennis shoes, a tape measure, a piece of chalk, and makes rules for the game. The tennis shoes represent conformity, and the fixed rules around Dante’s game is used to test the boundaries of that conformity. Later, Dante recalls their game in an elusive way, “All you have to do is be loyal to the most brilliant guy you’ve ever met—which is like walking barefoot through the park. I, on the other hand, have to refrain from kissing the greatest guy in the universe—which is like walking barefoot on hot coals.” The ideas behind being barefoot is determined by the situation. For Ari, the journey is painless because he is hiding himself from the world, which is a walk in the park, externally. For Dante, if he is expressing his sexuality openly and by himself, then the journey is painful because no one is there to support him. The symbolism continues in the novel when Dante and Ari are stargazing in Ari’s red pick-up truck. When it begins to storm, the two decide to undress and run through the open desert, but this time with their tennis shoes on! Alire Sáenz uses the shoes as a sign of conformity, but now that the two boys are freely expressing their sexuality; they have their tennis shoes on, giving us the impression that they are normalizing their affection. Two boys feeling affection for themselves is not an example of non-conformity in this world; it is a coming-of-age moment to be able to feel normal in one’s own shoes. Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe is a magnificent novel for the LGBTQIA community. It is perfect for young adult readers, especially if presented in the classroom. Benjamin Alire Sáenz presents a story of two average Mexican-American teens, set apart by their sexuality, only to have us realize the fluidity of sexuality and its normality. This novel is written with such candor on the subject of young men questioning their sexuality who are overwhelmed by the fear of other’s ostracization. Ari and Dante’s friendship creates envy for older readers, particularly those who had to make the journey barefoot over the hot coals of other’s disapproval. Benjamin Alire Sáenz creates this experience for those who are not so lucky to have a Dante in their lives. I recommend this novel for individuals looking for a guidebook through their own “inferno,” like Dante’s The Divine Comedy provides readers. |

|

Miguel is the Asst. Managing Editor and Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. As an editor, one of his main concerns is giving a space to marginalized voices, centralizing on narratives often ignored. He loves reading radical, unapologetic writers, who explore the emotional and intellectual stresses within political identities and systemic realities. His own writings can be found in OUT / CAST: A Journal of Queer Midwestern Writing and Art, The Rising Phoenix Review, and Rogue Agent. He writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog in Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >