- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

Brenda Miller & Lee Gulyas

Braid

Someone braided her hair this morning, or perhaps she’s learned how to do it herself, pulling the mass of hair to the side to ensure it doesn’t get caught in the loom. The braid is lumpy and thick, almost like an elephant’s trunk.

Her shirt is ruffled but missing a few buttons, and it’s a bit too small for her lengthening torso. Her arms are smooth and unmuscled, though surely she needs muscle to do this work. She’s either too tired, or too unpracticed, to smile.

The cloth she makes will be good. It will look like any other bolt of cloth, taken off the shelf, unrolled with a thump on the cutting table. When I was young, my mother would take me to Woolworths with a Simplicity pattern in hand; we wanted something to make the jumper pictured on the envelope. We’d buy a cotton blend, something that would last, with some kind of red flower—roses? pansies? poppies? —dotting the white.

We took it home, and my mother laid out the tissue-paper pattern on the kitchen table, carefully cutting the pieces with her sewing shears. I’d watch until I got bored, then wandered off to watch television until called back in for the requisite pinning. I’d stand on a chair while my mother measured the hem just to the bottom of my kneecap.

I thought nothing of the origins of that cloth, had no sense that real hands took part in making it—hundreds of hands really, if you counted the sowing of seed, the hoeing, the harvest. I just stood there in my suburban kitchen, the light steady outside on the cul-de-sac, and fidgeted inside the stiff pieces of a dress I didn’t even want. I wanted to go outside and play, like any other girl.

It was while I was running around, either on the street or on the playground, that I first noticed what it meant to be a girl. First, if you didn’t wear shorts under your jumper or skirt or dress, you couldn’t climb trees or swing on monkey bars or jump off the sloped roof of the shed. Not as long as you were playing with boys. They’d giggle, or worse, just stop and stare if your skirt flew up.

Inevitably one boy would say that he didn’t want to play with girls and I would slink away, my throat itchy and cheeks hot. I was mad at myself for being a girl, a girl who didn’t want to play with the other girls. All they did was stand around and talk about things I wasn’t interested in. Any way you looked at it, being a girl meant there was a long list of things you couldn’t do. Baseball? No. Astronaut? No way. Cowboy? Boy.

I was thankful for books. Nellie Bly, Florence Nightingale, Harriet Tubman, Elizabeth Blackwell: these women didn’t ask for permission, and they lived a long time ago. And even though I didn’t have to fetch water, pick cotton, or take care of my siblings—even though I attended school and was asked what I wanted to be when I grew up—I knew there were limits, but I wouldn’t know what they were until I came up against them, and when I did, I wouldn’t take no for an answer.

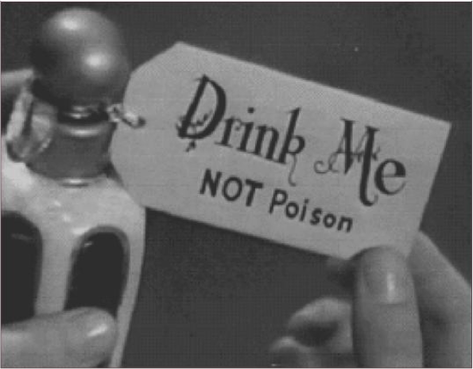

Choose Your Poison

My parents occasionally held cocktail parties, and I loved to help them prepare. Cutting cheese into cubes for fondue, arranging napkins on the table, and a quick dust mop of the parquet floors seemed exciting, even though I would be in bed before the guests arrived. I would lie in bed and listen to the music and voices and laughter while I drifted off to sleep. In the morning, there would be bottles and knives and citrus and cocktail shakers next to the sink, and I could smell the last traces of mystery and glamour before our lives became normal again.

Our lives were so normal otherwise—the daily routine of breakfast, school, lunch, and dinner. And what to drink often became the focus of everyone’s day—my father with his Ovaltine, me with my chocolate milk, my brother and his red Kool Aid. Always the first thing my mother asked--What do you want to drink? —and the illusion of control: opening the fridge door and standing there a long time as if the perfect drink might manifest itself from midair. I loved the idea of Alice’s potion, the command Drink Me!, the possibility of transformation in ways you couldn’t imagine. I wanted to be anything other than normal. I wanted to be filled with something beyond my control.

Waiting

As a child, I had small, square book embossed with the word Autographs in curly script across the gold cover. Inside, the heavy textured paper sat blank, waiting for who-knows-who to lay pen to paper and leave their trace. I understood the concept: an autograph is a souvenir, is proof that you stood in the presence of someone famous, someone you want to remember. Handwriting becomes the residue of the body—more personal, perhaps, even than a photograph.

But I didn’t quite understand the logistics: were you supposed to carry this book with you wherever you went, just in case you spied a celebrity, someone worthy of intruding on this creamy folio? I wish I could remember how or why I had it; we lived in Los Angeles, so it wouldn’t be out of the question to see a minor celebrity or two walking down the street, or in a restaurant, or getting out of a car.

And that girl, waiting. So brave, stepping up to say, shyly, May I have your autograph? Scribbled proof that she had, indeed, been in this person’s presence.

I know I must have collected a few famous names in my book, but mostly the pages became cluttered with autographs from my parents, my brothers, my friends. The ritual of holding the out the open book, proffering the heavy black pen that came with it, and intoning (with a slight British accent, as if this voice makes everything more important): May I have your autograph? And the autographer would consent, signing his or her name with a flourish: sometimes small, sometimes taking up an entire page.

I remember my mother’s handwriting: pretty and elegant, perfectly aligned. She used to write me letters, postcards, or chatty notes she included with packages, but I haven’t seen her handwriting in a long time now, everything replaced by emails and texts, everyone’s words looking exactly the same. How are we supposed to hold them now—the people we want to remember once they pass out of our presence? How do we collect them for future reference, and harbor the traces of their bodies when these bodies are gone?

So much of our lives are spent in the presence of other bodies, waiting. In lines at grocery stores or pharmacies. The DMV. A crowded bus stop or the security line at an airport. Those are the obvious, unavoidable instances, the easy ones we complain about, the weather of waiting conversation--hey that guy has fourteen items in the express line, or I’ve never seen such a long line here in the afternoon.

Other types of waiting aren’t so easily expressed. Waiting for that call to the office after your 7th grade math teacher confiscates the note you and Heather Herndon have been passing back and forth all day, that note where you both write down all the things that you want to ask, want to say, but can’t because there’s never enough time, and plus, you’re in middle school and don’t know quite how to talk about things yet. That time when you drove for miles with the cop following your every move, you behind the wheel, your friend in the front seat, a black male, both of you silent until the cop finally turned his lights on then made a u-turn, leaving you both still, silent for blocks. Being seventeen days overdue, huge and tired and ready (or so you thought) and doing anything you could to move things along—walking up and down stairs, mowing the lawn, moving toward that singular moment where everything would change. Waiting for Christmas morning. For the last day of school. The first day of school. Once the waiting is over and the anticipation is gone, what then? Was it worth it? Was it worth the wait?

--

Brenda Miller is the author of five essay collections, most recently An Earlier Life (Ovenbird Books, 2016). She also co-authored Tell It Slant: Creating, Refining and Publishing Creative Nonfiction and The Pen and The Bell: Mindful Writing in a Busy World. Her work has received six Pushcart Prizes. She is a Professor of English at Western Washington University, and associate faculty at the Rainier Writing Workshop.

Lee Gulyas’s work has appeared in journals such as The Common, Prime Number, Barn Owl Review, Event, The Malahat Review, Kahini Magazine, Tinderbox, Literary Mama, Sweet, and Full Grown People. She received a 2014 Washington State Artist Trust Grant, teaches at WWU in Bellingham, and has twice participated as faculty in WWU’s Service-Learning Study Abroad Program to Rwanda.

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >