- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

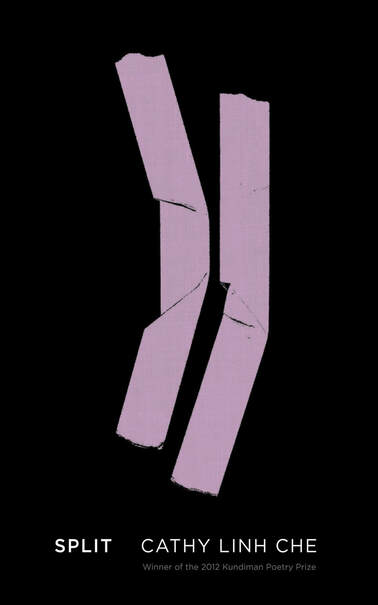

Book Review: Split by Cathy Linh Che

Cathy Linh Che is the author of the poetry collection Split (Alice James Books, 2014), winner of the Kundiman Poetry Prize, the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America, and the Best Poetry Book Award from the Association of Asian American Studies.

|

Review

|

A Review of Cathy Linh Che's Split

Cathy Linh Che is an excavator who does not hesitate to “dig in, / [until] the bloodlines emerge” when she unearths the transgenerational trauma that is “buried in the motherland— / somewhere in Vietnam.” Split is a triadic collection of poetry where Che’s speaker identifies as a “daughter, a mirror / … [and] a window” who compartmentalizes her life as both an eyewitness and a victim of violence. Part One centers on the speaker’s personal account of her “body’s disorderly circuitry” and the speaker’s sense of self. Che’s command of language can be seen in “In what way does the room map out violence?” Because all of the poems are written in first person, Split urges the reader to adopt the speaker’s hyperawareness as she navigates through her experience with sexual abuse: Not by force—just a shush in the dark-- This haunting excerpt unveils the effects of sexual exploitation rooted in a “family secret / ending in shhh.” Che juxtaposes the ordinariness of the speaker’s brother “check[ing] the toast” with the startling image of a child being sexually groomed into adolescence and the perversion of a sanctified marriage. Even so, the distress that sprouts from this experience becomes completely visceral once the speaker explains the molestation in detail:

He lifted his waistband and inserted my hand-- The speaker documents these disturbing acts by dissociating herself from the past in other compositions such as “[Doc, there was a hand],” “Profile,” and “The German word for dream is traume.” Part One summons and confronts the pain of memory as the speaker attempts to reclaim her innocence. By the end of part One, however, the speaker does not attain closure, which is depicted in “Story” when the she confesses, “My child-hand / has not grown up / since then.”

Serving as both a chronicle and a memoir, Part Two highlights the trauma of the speaker’s parents—particularly her mother. The speaker transitions from introspection to observance as each poem recalls Vietnamese history and its cyclical nature. Che addresses themes of war, violence, death, and displacement in “Split,” “First Day,” “In every psyche, tiny or dramatic perforations--,” “Daughter,” and “Self-portrait in Summer II.” In “My Mother upon Hearing News of her Mother’s Death,” Che’s speaker is cognizant of inheriting the burdens and trauma of her ancestors: I leapt into her mouth, her throat, her gut, and stayed inside with the remnants of my former life. I ate the food she ate and drank the milk she drank. I grew until I crowded the furnishings. I edged out her organs, her swollen heart. I grew up and out so large that I became a woman, wearing my mother’s skin. Che exhibits the double-consciousness of the speaker in this excerpt; the speaker hones in on her own autonomy and compares it to the generations before her—generations that are not only comprised of Vietnamese refugees, but of “village women pick[ing] up their girls” to escape “bị hại” and warfare.

In Part Three, Che’s speaker exhumes the shadows of silence in her epistolary piece, “Letters to Doc.” The speaker says, “I watched as my voice / was pulled from me,” and, in doing so, divulges the vulnerability she felt from being sexually assaulted. Che rewrites the speaker’s story of oppression into an empowering text that is “open / for all to see.” In “Gardenia,” the speaker rhetorically asks, “How must I attend to my life?” before reaching emotional release. The affliction she previously struggled with in parts One and Two is finally resolved in the following lines: I too can change. Che transforms the “memory or a wounding” of the speaker’s rape and “mother’s near rape / [which] was a recurring dream” into an archive of survival.

Throughout this collection, Che metaphorizes each line as “a bone / [and] each bone / a story.” Che’s work is a testimony that broaches the subjects of victimhood, violence, and self-validation with prudent sensitivity. The speaker exposes the complexities of the human experience and how inhumane transgressions can leave physical and emotional scars. Che beautifully captures the healing process the speaker undergoes after reopening personal, cultural, and historical wounds. Split is an artifact that bridges the narratives of the past, present, and future and needs to be handled with the respect it deserves. |

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >