- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

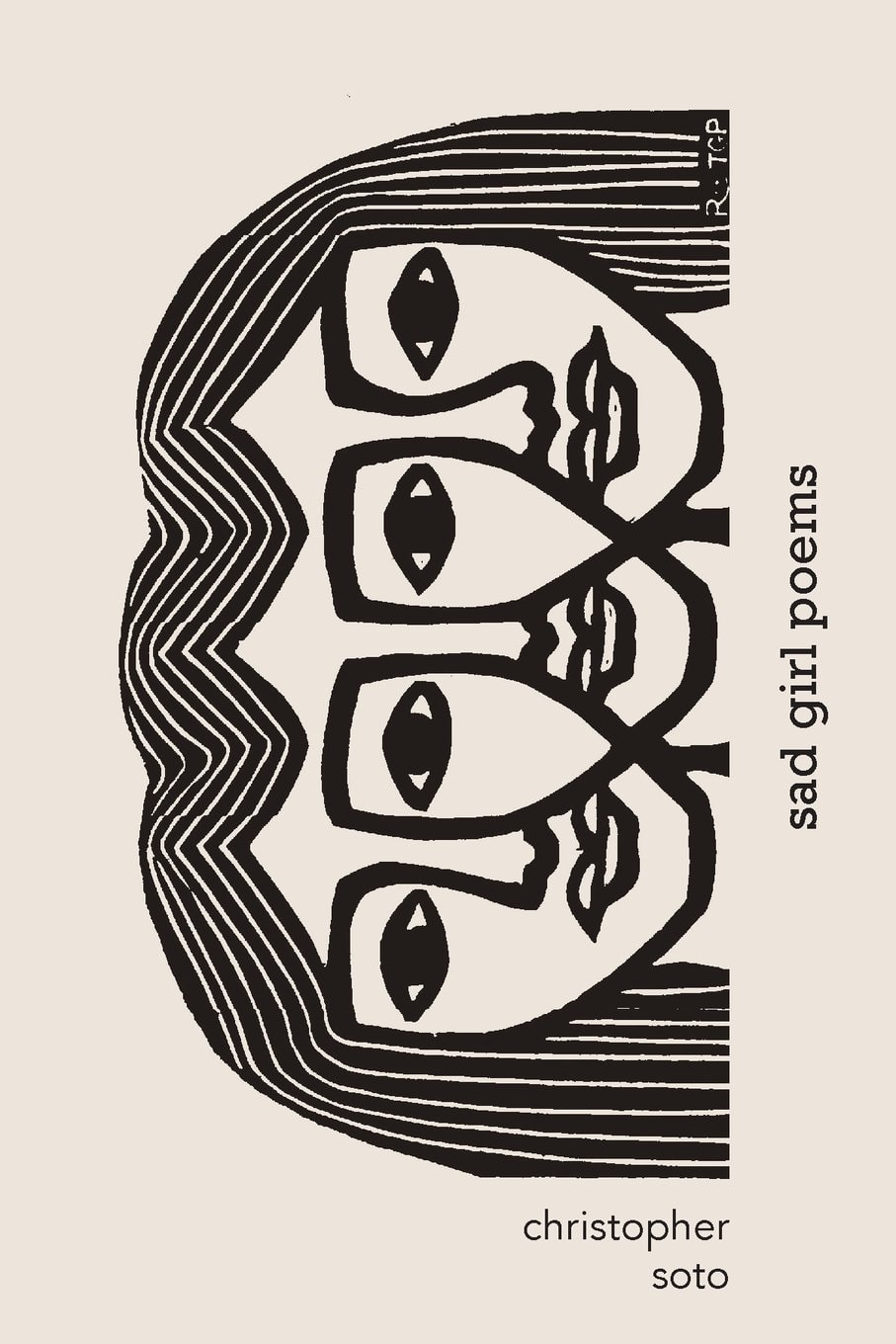

Book Review: Sad Girl Poems

|

Review

|

A Review of Christopher Soto's Sad Girl Poems by Miguel Soto

Christopher Soto’s Sad Girl Poems deal with violent, macrosocial issues, affecting young, queer, people of color. Soto’s narrative poems follow a traumatic past, referring to homelessness, familial abuse, gender identity, and the haunting, reoccurring voice of the speaker’s dead lover, Rory. In the preface, Soto makes their motive for writing clear, being that marginalized voices are so often muted in society. Soto’s poems transmit sadness into anger, and uses that anger as the fuel for mobilizing toward respect and dignity for marginalized voices. Their tone is direct and effective: Don’t just feel bad about our stories, consume us, & spit us out […] I want you to give your money to the Ali Forney Center & financially support queer homeless youth. I want you to donate your money to Black & Pink to support queer folks in prisons.[1] Christopher Soto’s narrative poems produce insight through the personal traumas they experience, demonstrating the vulnerability and power that comes from reclaiming voice from a silent isolation.

In “Those Sundays,” the speaker’s memory is taken over by two characters: their father and Rory. The beginning lines reflect negatively on the father: “he’d come / home with his cracked hands & bad attitude.” The memory of Rory interrupts the speaker’s negative view of the father: “I’d rather talk about Rory now […] / How the sun would comb crowns into / his hair.” For the speaker, Rory acts as an ideal escape from the familial abuse the speaker emphasizes. Specifically, in the fourth stanza, when the speaker calls to mind, “that night, after my father smashed / the television glass with his baseball / bat,” and the speaker seeks Rory, remembering, “[Rory] saw / my goose bumps from the cold. & / he felt my bruises, as they became / a part of him.” The speaker’s connection with Rory imparts empathy, drawing on the pattern many queer youths of color face within their families, and their desire to connect with others facing the same issues. In the fifth stanza, the speaker intends to “carry all the burden,” for both themself and Rory, but the only consolation the speaker can offer is, “nobody has to know about us, not my father / not yours— / No, not even God.” The final line of “Those Sundays” exemplifies the secrecy that grows between queer youths of color, who feel safest outside of everyone’s and everything’s periphery, demonstrating the start of marginalization at home, and then the way that forced isolation develops into constant fear and anxiety. Although the narrative is personal, the experience reflects many queer people of color, exacting a critical examination of familial dynamics, while demanding the safety of queer youths of color to be a priority. Another aspect that extends from familial dynamics is the speaker’s contemplation in “I Wonder if Heaven Got a Gay Ghetto.” The subject is a queer person of color’s position within religion, referring to two acclaimed writers to support the perspective: Lorde know(s) cis-hets don’t like me. The references to Audre Lorde and James Baldwin reinforce the decades of theoretical research and analysis put into criticizing society’s view against queer people of color, and the anger that comes from having to pick-up and further the work that both Lorde and Baldwin put a lifetime into. The speaker augments their point by revolutionizing the way readers think of people who adhere to the gender assigned to them at birth, and follow a heteronormative orientation: “cis-het.” The word choice opens a dialectic between gender conforming and gender non-conforming people, acting as a tool for visibility for queer and gender non-conforming people. In the conversation between gender conforming and gender non-conforming people is the need for refuge from violence that “cis-hets” enact on queer people of color, so much so, the speaker believes not even death would free them from the fear and anxiety that comes from living in a cis-heteronormative society.

Soto’s voice remains active throughout all their poems, calling to action people’s attention, intending to mobilize readers for the needs of queer people of color. In “Ars Poetica,” the speaker’s poetic art is to create and fuel activism: “I want everything to have purpose— / the beak, the bones, the baby blue / Vodka veins,” and yet the speaker confesses, “this is such a useless fucking poem.” The speaker admits to the emotional exhaustion that comes from narrating the experiences of themself and Rory, especially when the experiences meet an intersection of complacency and carelessness from others. The speaker further confesses, “None of this is about Rory / it’s all about me,” making the reader question the speaker’s transparency, being reflective of the way the speaker must question their reason for writing. There is insight in acknowledging self-interest, especially since the speaker discloses Rory’s death in earlier poems, allowing the reader to understand that the speaker’s own survival translates to the survival of other queer people of color. The mode of self-interest illustrates where fear emerges from, when the pain of Rory’s reccurring memory appears, clarifying the cryptic relationship between the speaker and the speaker’s memory of Rory. Christopher Soto’s Sad Girl Poems relate pain and sadness—as it intends to do, influencing readers to react and respond. The narrative poems Soto speaks through, move and fluctuate emotions, forcing radical change in language, feeling, and action. Soto’s collection of poems is ideal for the reader searching for a method to sublimate feelings of anger, exhaustion, sadness, and despair with living in a cis-heteronormative society that refuses to easily accept the existence of queer and trans people of color. Christopher Soto’s Sad Girl Poems confess and despair, but continue to breathe through the living queer bodies of color, adapting to survive every day. [1] Link to donate and support the Ali Forney Center: https://www.aliforneycenter.org/get-involved/, and a link to donate and support Black & Pink: https://secure.actblue.com/contribute/page/blackandpink |

|

Miguel is the Asst. Managing Editor and Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. As an editor, one of his main concerns is giving a space to marginalized voices, centralizing on narratives often ignored. He loves reading radical, unapologetic writers, who explore the emotional and intellectual stresses within political identities and systemic realities. His own writings can be found in OUT / CAST: A Journal of Queer Midwestern Writing and Art, The Rising Phoenix Review, and Rogue Agent. He writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog in Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >