- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

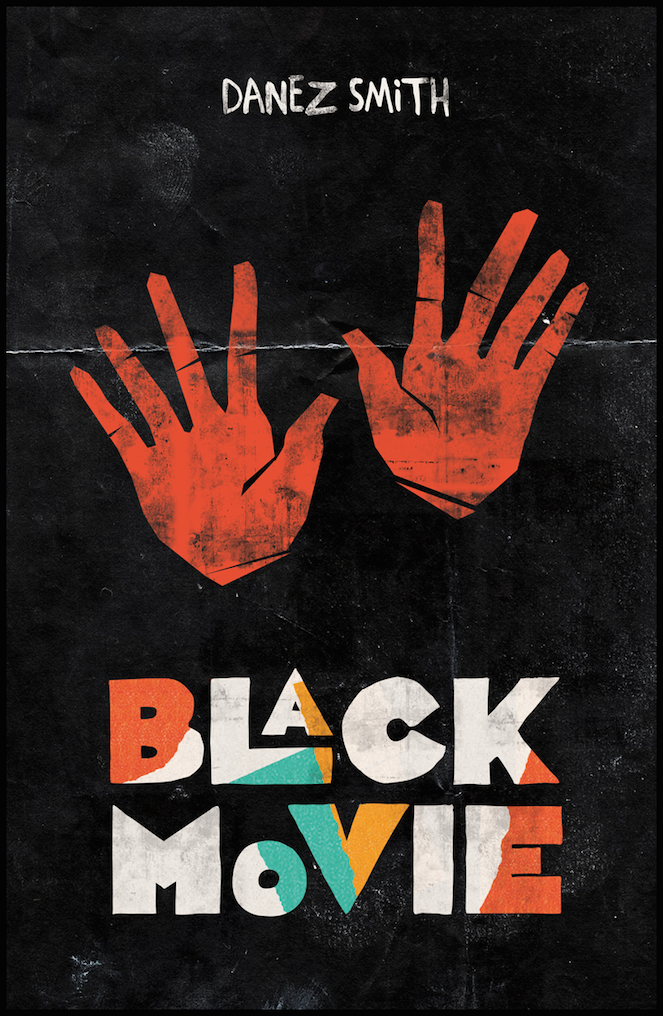

Book Review: Black Movie

|

Review

|

A Review of Danez Smith's Black Movie by Miguel Soto

Danez Smith’s chapbook Black Movie challenges large media outlets and film that devalue and misrepresent the black community in the United States, using direct and didactic metaphors, which do not allow themselves to fall into ambiguity, that would, in turn, need heavy interpretation, and risk being a form of misrepresentation. Readers are fixed to the poems, facing the harsh inequalities that burden our society, revealing overused tropes for black people in films, reflective of the brutality imposed on black bodies. In Smith’s opening poem “Sleeping Beauty in the Hood,” Smith introduces two juxtaposing characters, setting a distinction between fantasy and reality. The allusions to film culture, especially Disney’s film adaptation of Charles Perrault’s fairy tale “Sleeping Beauty” and Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood, set up the distance between the imaginative roles people wish to fill, and the reality of existing in a marginalized community. When “townsfolk / name themselves Prince Charming,” attempting to “wake the sleeping beauty,” wishing to embody the heroic trope seen in Disney films, it becomes disheartening when the main character “Jamal” embodies the sleeping beauty, and cannot be revived by the people who wish to be Jamal’s hero. The response to “Jamal won’t wake up” is “You mad? This ain’t no kid flick. There is no magic here,” realizing the situation is a clear representation of the young black folks dying at the hands of systemic inequalities, i.e., disproportionate use of money to fund neighborhoods (“hood”) and the police brutality that this scene foreshadows, which is more prominent in the following poems, but forces the reader to take responsibility over their expectation of thinking they would be met with a happy ending. In “Boyz n the Hood 2,” the speaker of the poem erases any possibility of expecting a happy ending, stating, “let’s not mention the original,” because the poem is “a series / of birthday parties for the child / who lives in the picture frame.” The allusion to Boyz n the Hood further illustrates the lack of attention and care the United States has for people who live in marginalized communities, like the hood, which was the film’s original purpose when it was released in 1991. The exposition no longer rises to the experience of loss and grief but is in a constant and endless state: “Every year we watch the family / watch their home burn to the ground. / The movies get old. The boy never will.” The sentences’ structure is short and personal, leaving the need to hide grief in metaphors and symbols behind, showing that subtlety and passiveness are not the tools for drawing our attention and treatment to the communities in subject. Black Movie grounds the reader’s attention to the black community and police discrimination that persists on brutalizing black bodies. The poem “Short Film” provokes the famous poetic form, the elegy. An elegy being an appropriate response, given the recent deaths of Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Renisha McBride, and Brandon Zachary, who are all alluded to in the poem, but it is the lack of resolution that keeps Smith from writing them into an elegy. An elegy needing three major components, lacks the third, consolation and solace. Smith’s “Short Film” begins with a profound question: “how long before / a legend / becomes / a god or / forgotten?” The question stretches into an answer: “think: once, a white girl / was kidnapped & that’s the Trojan War,” leading to the situation that calls for a monumental war in the name of justice, “Troy got shot & that was Tuesday. are we not worthy / of a city of ash? of 1,000 ships / launched because we are missed?” The response criticizes the prioritization white society takes in demanding justice for the injustice and inequality done to white people, but won’t respond to the same when the injustice and inequality are in the face of black people. When writing the section “iii. not an elegy for Renisha McBride” within “Short Film,” Smith describes the last moments before McBride’s death, “a myth of the bullet, the red yolk it hungers to show her / or the tale his hands, pale & washed in shadow / for they finished what the car could not.” Smith does not deviate for a moment from the brutal death McBride met when, in 2013, she left her crashed car searching for help, yet no police arrived on the scene, even after 911 dispatchers were contacted forty minutes before she knocked on the door of a fearful white man whose shot ended her life. Smith ends her section with, “if I must call this her fate, I know the color of God’s face.” Not only is Danez Smith challenging readers to accept that Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Renisha McBride, and Brandon Zachary, all lack an elegy because of the dominant society’s lack of consideration, but he also deviates from using the “standard” set of rules for the English language, refusing to capitalize letters in the Roman numerals, in titles, and after using periods, indicating a deviation from the colonizer’s language; and, by proposing God’s face is white, since the oppression of black people persists after the colonizer’s introduction of Christianity, which still allows the subjection of black lives in this century. The techniques factor in audiences’ responses, using the opportunity to steer the reader’s attention to the black community, demanding the justice and respect they deserve, so those who have passed can receive a proper elegy. Danez Smith’s main goal in challenging the stereotypes and tropes found in films, which exploit and capitalize on black bodies, is to challenge the prejudices that are formed from taking the misrepresentation as truth. In “Scene: Portrait of a Black Boy With Flowers,” the speaker’s first line is, “& he is not in a casket,” following the line, “he does not return to dirt,” and then the lines, “he does not bring flowers / to his best friend’s wake,” taxing the reader’s expectation of death when a black person is present in a film, questioning the intent of filmmakers, who consistently correlate blackness and death. Instead, the scene is simple and graceful: “the boy is in his aunt’s garden / & the world does not matter,” closing the scene with, “pollen dusts his skin / gold as he grows.” The boy in this poem deviates from society’s backward prejudices of black boys and men, demonstrating a branch of narratives and experiences, which test the notions of a collective experience among black people. Danez Smith’s Black Movie scrutinizes the false stereotypes and tropes film and media perpetuate. The language found in Black Movie undercuts the need for complex interpretations and metaphors, which often distort reality and the truth, making the message clear-cut, being that society is far from equal and that black people demand a stop to the oppressive forces that prolong police brutality, misrepresentation, and invisibility. Black Movie is for the reader who is ready to take responsibility for their language and actions that often preserve oppressive practices and ideologies, making this a perfect collection of poems for self-education and realization. |

|

Miguel is the Asst. Managing Editor and Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. As an editor, one of his main concerns is giving a space to marginalized voices, centralizing on narratives often ignored. He loves reading radical, unapologetic writers, who explore the emotional and intellectual stresses within political identities and systemic realities. His own writings can be found in OUT / CAST: A Journal of Queer Midwestern Writing and Art, The Rising Phoenix Review, and Rogue Agent. He writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog in Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >