- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

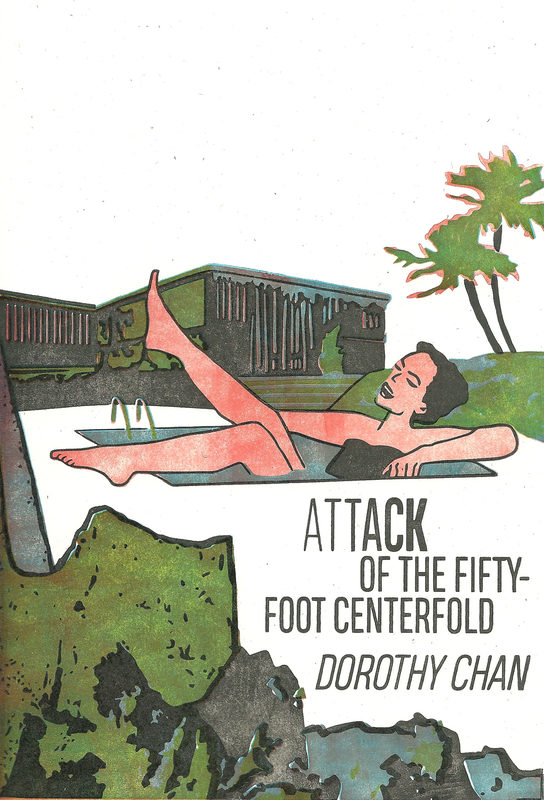

Book Review: Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold by Dorothy Chan

Dorothy Chan is the author of Revenge of the Asian Woman (Diode Editions, Forthcoming March 2019), Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold (Spork Press, 2018), and the chapbook Chinatown Sonnets (New Delta Review, 2017). She was a 2014 finalist for the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship, and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Academy of American Poets, The Cincinnati Review, The Common, Diode Poetry Journal, Quarterly West, Jet Fuel Review and elsewhere. Chan is the Editor of The Southeast Review and Poetry Editor of Hobart.

Chan is currently a PhD candidate in poetry at Florida State University. She received her MFA in poetry at Arizona State University and her BA in English (cum laude) with a minor in History of Art at Cornell University. |

Review

|

A Review of Dorothy Chan's Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold by Miguel Soto

Dorothy Chan’s Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold is a collection of poems in three segments: “Snake Daughters,” “My Chinatown, a quadruple crown of sonnets,” and “Centerfolds, Histories, and Fantasies.” Each segment contains an actualization of the speaker’s self, and their position in Chinese-American culture, finding an abundance of beauty and appreciation. Through the satirical mode in each speaker’s voice, Chan delivers a vivid experience of Chinese-American culture, food, and womanhood. The speaker’s experiences is a realization of sexual manifestation, giving into, controlling, and owning the lustful appetite that develops in many human beings. In Chan’s first section, “Snake Daughters,” the poem “Ode to All My Flings Who Hated Dim Sum,” is a celebration of Chinese-American culture, serving the reader plates of food, history lessons, and sociopolitical critiques. The poem’s first two stanzas are loaded with flavor, which the speaker points out her past “flings” are constantly missing out on: And they’re missing out every time I order Food becomes crucial in many of Chan’s poems, as food is the center point for the speaker’s own realizations when it comes to how people respond to the food she presents them to, or even more simply, the celebration and joy that comes from being in the presence of familiar foods. Chan's speaker in “Ode to All My Flings Who Hated Dim Sum” assures the reader and her past “flings” that the issue is not with her cuisine, but the “flings” themselves: “these men / can’t handle the truth that this isn’t Bizarre Foods for me.” In countering the comments and gestures the speaker’s “flings” make, she adds a feeling of both exasperation and humor for having to deal with the ignorant remarks of the “white boys” she brings into her comfort zone:

and no, white boy, you can’t handle my food, The speaker refuses to be the object of Anglo-American misperceptions and stereotypes, rejecting the sexual fantasy imposed on her. The last line subverts the fetishizing of “softest skin” with “sandpaper,” mocking both the “white boy” and reader for thinking Chan's speaker ever even cared about being accepted into the confines of the ‘proper’ etiquette often imposed on women, especially non-white women.

Moving into Chan’s second section, “My Chinatown, a quadruple crown of sonnets,” the poems connect between historical backgrounds, Chinatown square, family, food, and a multitude of vivid memories, creating mini vignettes of experiences as a Chinese-American in the U.S. Chan’s segments are full of rich stories, critique, humor, and emotional range. In “Welcome to the Family,” the speaker amuses a “High Roller of Hong Kong’s Happy Hour” for a while, considering commitment versus passion. While the “High Roller” decides to meet the speaker’s grandmother, her displeasure shows in her comical stance: Is this the 21st century romance of The poem’s rhetorical question examines the authenticity of the commitment ensuing. The speaker entertains the unnamed “High Roller” out of commitment, but her own disinterest surfaces, revealing her refusal to accept the fabricated “love story.” Chan’s section “My Chinatown, a quadruple crown of sonnets” sticks to the fourteen-line form, but is transformative in line variation, theme, and subject.

Progressing into the third section, “Centerfolds, Histories, and Fantasies,” Chan’s titular “Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold with the Killer Legs” encompasses the titillating motifs throughout Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold. The speaker’s purpose throughout each poem reclaims sexuality from objectification, refusing to be the object of the male gaze; instead, choosing to be the subject that she commands to be, because “this is LA, and women will have it all.” The "centerfold" proves how she commands her surroundings, coming down from the billboard, and stating, “King Kong only needed Faye, but a woman like me needs one hundred men.” The speaker’s authority “attacks” expected gendered conventions, shifting her position from the desired object as Faye, to the attacking giant, becoming the subject, but with the ability to direct the scene: my men run to Fredrick’s to pick up Chan’s “centerfold” demands and directs the attention of the scene, displaying autonomy over her own body and actions, and demonstrating the agency earned in refusing to be degraded by the men on their terms. The “centerfold” speaker exercises her influence over the men and scene: “I dare ten of them to lick me, but they freeze / at my womanhood.” Chan’s direction over her lines and language illustrates the unexpected turns of what she asks for, and what is actually acted on. Chan’s control over her lines conducts the shift in emotion, being able to depict the satire behind the significance of the “fifty-foot centerfold.” Instead of allowing the giant “centerfold” to run with bewilderment, the “centerfold” owns her sexuality, and knows exactly how to work it in her favor.

Dorothy Chan’s Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold is a journey of accomplishment and acceptance of the poems’ speaker’s Chinese-American origin, sexual fruition, and dominion over appetite. Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold is for the reader looking to experience the fulfillment of living in complete control over one’s own body, fears, desires, and oppositions. Dorothy Chan creates a world where her lead woman lives just as she pleases, and her pleasure becomes the reader’s own pleasure. |

|

Miguel is the Asst. Managing Editor and Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. As an editor, one of his main concerns is giving a space to marginalized voices, centralizing on narratives often ignored. He loves reading radical, unapologetic writers, who explore the emotional and intellectual stresses within political identities and systemic realities. His own writings can be found in OUT / CAST: A Journal of Queer Midwestern Writing and Art, The Rising Phoenix Review, and Rogue Agent. He writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog in Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >