- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

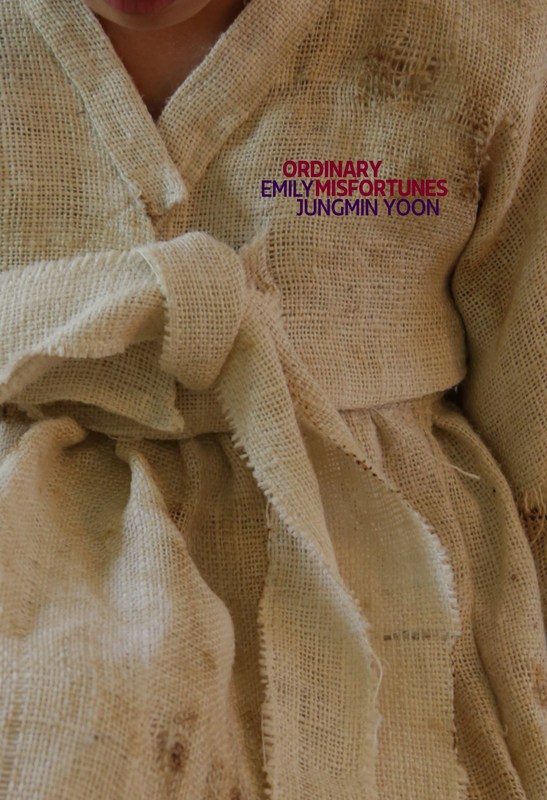

Book Review: Ordinary Misfortunes

|

Review

|

A Review of Emily Jungmin Yoon's Ordinary Misfortunes by John Darr

The Power of Vocal Unity in Yoon’s Ordinary Misfortunes Throughout her debut chapbook Ordinary Misfortunes, Emily Jungmin Yoon achieves historical glossolalia. While it is common practice to speak for others through poetry, Yoon’s deft weave of her personal narrative with those of past survivors grants her collection an accomplished multiplicity. The honesty and respect inherent in Yoon’s language anchors her treatment of each delicate historical perspective. Yoon’s central focus is the tragic account of Korean ‘comfort women’ enslaved and repeatedly raped by the Japanese military during World War II. In many cases, she uses of documented language from survivor interviews to respect the barriers of understanding between direct and indirect victims of tragedy. Yoon’s faithful poetic reproduction of their stories, largely sourced from video interviews with the survivors, intertwines seamlessly with her own account as a Korean-American living with the burden of her country’s history. This balance is established in opening poem “News,” which reflects on the tragedy of the MV Sewol in a scene of domestic normalcy: “There’s an article on how to eat an apple / But I am eating a pear and thinking / pear in Korean is a homonym for ship or boat / and stomach…” Ordinary Misfortunes demonstrates Yoon’s incredible ability to jump between present reflection and historical account while also questioning the ability of language to do so. The masterful voice inhabiting Ordinary Misfortunes also finds breath in Yoon’s restrained yet effective formal choices. Her prose poems, all titled “An Ordinary Misfortune,” consistently assert the existence of a narrative out of seemingly disparate pains: Yoon winces at her country’s history, her country winces back. Yoon’s navigation of this territory is by turns brutal (“Hands full of girl. Fields full of gravel. Korea is gravel and graves.”) and heartbreaking (“War hasn’t left Korea. I have.”), yet always geared towards creating images of troubled unity (“She offered him head because he wanted her whole.”) Through the prose form, the reader is forced to absorb twin histories as a formal narrative, further intensifying the friction between the accounts Yoon conveys first- and secondhand. However, the interplay between form and content acts as more than a simple contrast between narrative types. This is apparent from the very beginning of the chapbook. In a deceptively complex formal choice, Yoon constructs “News” as a concrete poem. While the shape of an arrow pointing into the rest of the collection may seem obvious, it draws attention to the unconventional order of events in the text. This form doubles down on Yoon’s decision to use the Sewol as a starting point for her exploration of tragedy despite its occurrence long after the comfort women atrocities. Her other poems deliver on this promise effectively. While the tragic loss of hundreds of nameless children offers a foundation for loss that seems difficult to build upon, Yoon’s following testimonies grant credence to the value of individual human beings that continuously makes the impact of the initial tragedy more visceral and painful. The accounts of each woman in the “Testimonials” section of her chapbook attach a plethora of names to the collective narrative of tragedy: each woman’s narrative begins in different ways and yet as each nears the same horrific conclusion of abuse, they become unignorable screams in a collective whole. The unity in Ordinary Misfortunes remains striking even for a work of its brevity. In a brilliant turn, Ordinary Misfortunes turns its eye outward during its final poem, expanding its scope without resorting to a cliché of overt hope in the face of tragedy. Closing poem “The Transformation” mirrors opening poem “News” by introducing a new tragedy separate from the narratives in the core text. Yet this time, the tragedy has a non-human victim – a group of whales beached after ingesting litter. “I was once naïve enough to be a woman,” begins Yoon, diving into the shipwreck of her own human perspective and lifestyle. By taking on the perspective of the beached whale as her own, Yoon reframes the act of beaching becomes a sort of homecoming to humanity. The scene is filled with ecstasy and recognition in spite of the starvation that leads there. This bizarre, joyful loop of animal sympathy and human reincarnation celebrates unity in the face of pain and death. The chapbooks last line gesture grandly towards the conflicted scene: “Look, such slender beauty of things. / Shadows, leaves, rows of clouds pushed / by some animal wind.” The pain and destruction to which Yoon’s voice testifies may be unavoidable and undeniably human, yet so is the tendency to come together and speak when silence threatens to erase records of collective suffering. |

|

John Darr is a poet, music critic and educator from Richmond, VA. He is currently the Poetry Editor for the Mikrokosmos/Mojo literary magazines and his work was most recently published in SOFTBLOW and Virga. He is currently an MFA candidate at Wichita State University where he teaches English Composition.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >