- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

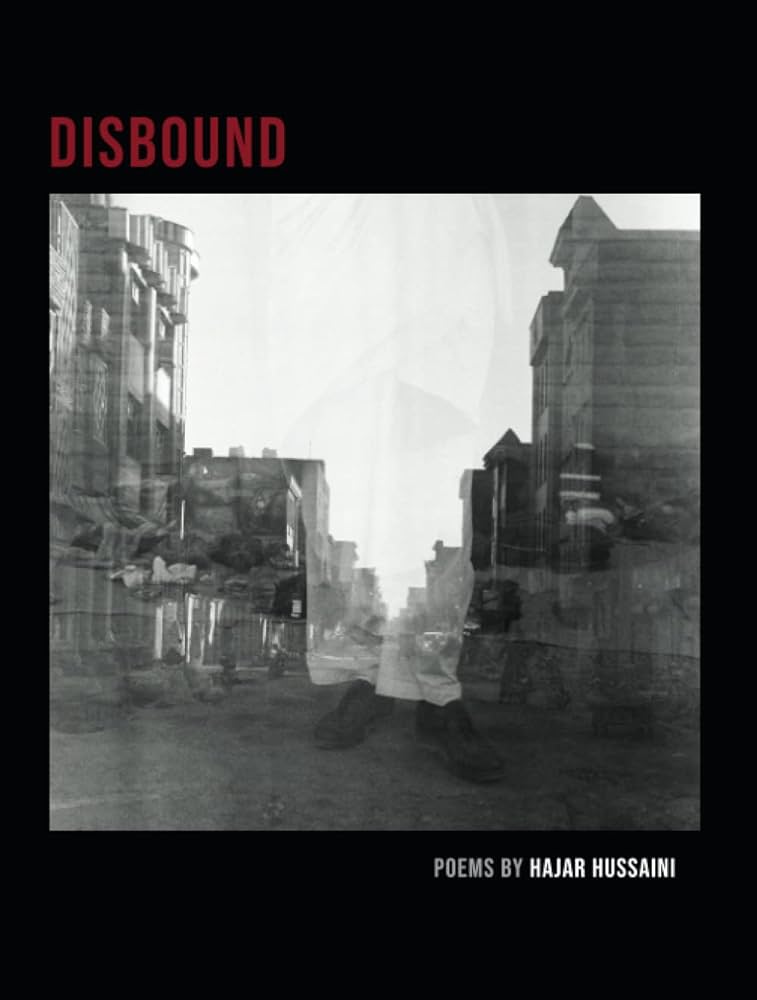

Disbound

|

Review

|

Stone, Scissors, or Paper

On Disbound by Hajar Hussaini There are objects we must break before using. Books as physical objects belong to that realm. There are the book covers we fold three sixty, the spines that come off like new ballet pointe shoes we smash against the floor only to pick up and peel off their instep. Disbound, Hajar Hussaini's first poetry collection, published in 2022 by the University of Iowa Press, asks us to take a vow of faith in its name, and imagine that what we hold in our hands was previously collected and now has lost binding. Its title commands us so-–the act of dismemberment— if we approach it in its imperative reading. Form, then, gives us time: the book begins after its disintegration. "The fall of Kabul was so intense," says Hajar Hussaini regarding the events that transpired in August 2021, a disposable coffee cup between his hands, "that I couldn't not engage with it. My relationship with Kabul was contingent, it happened and then I became an exile," explains the Afghan poet. Disbound is testimony to a body that lost molding, a disintegrated memoir where rocks, paper, and scissors invert, disarrange, cut where there is no paper, and crush something that long ago lost edge. The book warns us from the dedication: "for the sisters without whom I have no meaning". The self, that collective that was once amalgam, splits into distances, the words become embedded in the pages given to us. The first poem, for instance, is the sequence that lost the order of the game: notes from Kabul on being fine when others aren’t; notice graphic, how quotes wax truth & assassinate anecdotes the surplus of survival guilt covers pages & the data at the price of two boiled eggs rectangular streets grind us like watercolor powder we wash blood off bags & hats & the few branches of tree are un blaze yet we still play stone scissor paper In Kabul, there are two intellectual groups. One camp was the Persian-philes. Educated in Iran, they came back to Afghanistan. They read Iranian literature, and made their living by small businesses, journalism, photography, sometimes art. They are the gatekeepers of Persian. The other camp were the people who were part of the diplomacy, the government elite, those who benefited directly from the US government. They were educated in Pakistan, the children of former leaders, they came from the West, “they drank alcohol because alcohol is expensive. They are culture consumers.” Although Hussaini does not belong, under the headings of ancestry, to any of them as such, her poetics does drag linguistic sediment from both sides. From the year she was born, 1991, to 2003, Hussaini lived in Qom, Iran, two hours away from Tehran. “We were in the periphery,” says Hussaini, her coffee growing cold, “we thought the war was over when the US invaded Afghanistan. That's why I use images of my body as a metaphor for what has happened to Afghanistan." One of the meandering streams along the books is that of the transformation of shapes: a kind of transubstantiation: “before owning our cellphones/ we were two mothers,” reads one of the poems whose embroidering of womanhood breeds into the language. The book is a recollection, a Persian etymology, a road trip, a funeral, the field of death, a simple cafe, a self-checkout chorus, a meta-variable self-parody where “the hyphen belongs to an element feeding off cord one attempts and aborts.” The history Hussaini attempts is that made from the everyday life of people, not the approach to Afghanistan that we have today: that which filters through specific events: either the Soviet invasion, or through the United States intervention. "You get away from the people if you look at it through specific events, as if Afghans don't make their own history,” says Hajar, her eyes decisive, transfixed by words. Disbound is a commentary on form. A child’s game gone whose actors, just like their chanted spell, lost the order of things agreed upon: the scissors sliced what was written on paper. Like the language it collects, corporate words with new poetic inflexions, Disbound is also bureaucratic, a collector of ruptures that compromises its own title: although the printed words, when bound, are collected, and assume an imposed sequence in their concatenation, the book begins by prefacing our reading of its pages: this is one of its many orders, an order composed by units of paper and ink that were, one can assume, previously, and ultimately, scattered. |

|

Moriana Delgado is a Mexico City writer. Her first poetry collection, Peces de pelea, came out summer of 2022 with The National Autonomous University of Mexico Press. She graduated from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in spring of 2022, and she is currently a PhD student at UIC. She writes a monthly newsletter called ‘Alone at the Party.’

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >