- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

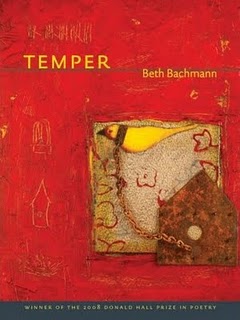

Interview with Beth Bachmann

This interview with Beth Bachmann about her collection Temper was conducted during the summer of 2011 by the following poets: Danielle Burhop, Aaron Delee, Dane Hamann, Sarah Jenkins, Anthony Opal, Christine Pacyk, C. Russell Price, and Lana Rakhman. It first appeared on Sharkforum and has been preserved here.

|

Beth Bachmann Biography

|

Beth Bachmann's first book, Temper, was selected by Lynn Emanuel as winner of the AWP Award Series 2008 Donald Hall Prize in Poetry and won the 2010 Kate Tufts Discovery Award. Her new manuscript recently won the Poetry Society of America's Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award. Read an excerpt here.

|

Interview

|

Many of the poems in the book feel restrained, in their messages and by the form (or in their lengths); you're always edging onto something, but cut away from it quickly. So, much of the book reads in what is not being said, rather than what is stated; the confusion, the mystery surrounding its central drama. Is there a particular reason you chose this route over lengthier and expository poetry? Bachmann: I love the short lyric form: Dickinson, Rilke, The Book of Odes. I have a strong appreciation of silence. And in a poem, of staged space. You pay great attention to detail in the poem, akin to a forensics officer. Even your use of language reflects this, such as in the first line of "Lineup": God pointed his finger and said step out of this body: the guy who makes his bed from a ream of the free papers and squats at the depot, the janitor in charge of public toilets, the drunk Noah, an anonymous ignudo, my father. Given such distinct choices in words, I was wondering if you had any words that you considered overplayed in poetry/that you might steer away from or ever rethink before using? Bachmann: A list of words off-limits in verse? I just received ED spam titled, your nether attacker. I'd probably avoid that phrase. Also, the word numinous. It's a good idea to consider each word at least twice. In interviews you have said that you titled the collection Temper before writing the prologue poem "Temper." How did you come to Temper as a title, and why did you feel you needed a poem with the same title in the collection? Bachmann: I wanted to slow the pace down, light the fuse before dropping the bomb. The word temper has the looking once and looking again I wanted; it's a seesaw, in terms of balance. There is an important balance of personal and forensic details in your poems. How mindful were you of this balance when you were writing individual poems, and then when you were organizing the collection? Bachmann: Forensic comes from forum, a public place. A purely private collection likely wouldn't be of interest to anyone, not even me. I suppose part of the art of a poem is getting someone else to read it. Thanks for reading it. In your interview with Nashville Review, you told how you had written one poem, "First Mystery of My Sister," and you were encouraged to go/write "deeper," which led to "Paternoster" and the rest of Temper. What was your process for writing deeper? Bachmann: It was simple, in that I decided to finally enter what I'd clearly been moving toward. Deciding to jump's the hard part. Falling: easy. Many of these poems have appeared elsewhere in literary journals, but now that they've been published as a book, do you believe that each poem can stand alone? One of the things that stood out in this book was the consistency. Is the consistency too strong to separate these poems? Bachmann: I was just reading Rilke: Whoever has no house now, will never have one. /Whoever is alone will stay alone. Taking the objects out of the house doesn't change the objects, but it changes the room. In many ways you have created a complex and exhaustive landscape in this book. The panorama of violence, death, accusation, guilt, and innocence encircles the main focus of the book. As readers, we move by each tiny detail, learning past histories and cataloging the way these things have come to rest. What was your process in creating this landscape and how did you approach this process without drifting into mystery writing? Bachmann: I always wore my seatbelt and did not text while driving, avoided large machinery while drowsy. Clearly, I'm not high-risk for drifting into mystery. The process is bit by bit. Same field, a hundred things to do there. In your collection of poems Temper, most of your poems are composed with long lines and you even include two prose poems. During the initial draft of a poem, does the form present itself to you as a means to experiment, or is form secondary to either the language choices you make or the thematic significance you're going for? Bachmann: They happen at the same time and one follows from the other: pacing, subordination, weight, surprise. In another interview you mentioned that you originally studied photography, which is hinted at through the vivid and often startling images in Temper. How do you think your work as a visual artist has impacted your poetry? Have you ever thought about merging the two art forms? What do you think this could mean for your poetry? For your photography? Bachmann: Oh, I gave up photography around the same time I picked up poetry, though I did shoot a short black and white film of Nick Flynn reading Tony Hoagland's black and white poem at AWP for my private archive. Photography involves a lot of waiting for light. Poetry is more immediate and independent of others for the movement and intonation I desire. Bergman's in my ear saying again. Again. Again. the girl the fawn strips like a fisherman's rose where a female crawls/ to birth a litter the opossum's tongue grazes her lip something is always// moving, suggesting a harness muse: an open mouth,/ a muzzle There is a motif of animals in your work, both wild and tamed. Wild animals are a natural part of the landscape you describe here, but your choices are striking: it is not a coyote that feeds on the body, but a fawn; the opossum's meeting with the body seems quiet, reverential. Conversely, you introduce words like muzzle, and harness, which you apply to human behaviors: speaking the word muse, or "mining the sky/ to generate light". These choices, to me, seem to invert the expected: the need to control untamed behavior through muzzle or harness is transplanted from animals to humans. Was one of your goals with this collection to reclaim and question nature - to ask the reader to re-evaluate the essential qualities of life? Bachmann: I'm looking at extreme acts of violence, what we might be tempted to call inhuman behavior, but what might be more readily human nature. So, yes, the big questions: what makes us human? What to do with the animal in us? And how the human act of writing is attempting to harness these questions. Your collection contains constant movement and transformation of the speaker. There's the accumulation of knowledge which mirrors the heaven-to-hell progression, as well as the personal journey of the reader in real time with the speaker's. When you set out to write this piece, how did you decide to order it? Did you have a basic structure in mind or did one poem spark a series and then suddenly you had a constellation of poems? Bachmann: One poem sparked another, more like flowers, weeds, the beasts in between, but, in the end, I had to think more about the art of the garden, how to move the visitor through it, which again has to do with pacing, pause, light, competition, color, shade. What I love most about Temper is your ability to portray such vivid details without having to use any proper nouns whatsoever. The setting as well as characters become universal through their non-descript monikers such as sister, janitor, and the men at the club. Because this collection is so personal, why were there never any names (places or people)? Bachmann: I always conceived of it as a collection about violence, not about a person or place. Names seem irrelevant to the project. How did you choose the order of the poems? How did you put the poems into sections, and what were your thoughts when forming the arc of the book? Bachmann: I love the order of Tokyo, the gardens of Kyoto. You focused entirely on your sister's murder, instead of on your sister's characteristics, which makes for an intriguing read. How did you manage to veer away from the sentimental, even though you are so close to the subject matter? Bachmann: My end goal was never memorial. If it's elegy, it's lamentation or howl. What is your understanding of the poetic line-- is it primarily sonic, visual, rhythmic-- and how does this understanding inform your writing process? Can you talk specifically about your use of longer, syntactically broken lines, opposed to shorter, enjambed lines? Bachmann: That's a tough choice. I'd say it's primarily about pause, which is all three. I suppose the length of my line is determined by how long I want to hold a gaze and who's the first to break it, and then the lure, linger, and consumption. What are your thoughts on MFA programs? How helpful has outside criticism been to the development of your poetry? Bachmann: Very. I wish I had an MFA. |

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >