- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

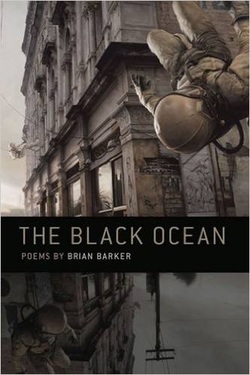

Interview with Brian Barker

This interview with Brian Barker about his collection The Black Ocean was conducted during the summer of 2012 by the following poets: Aaron Delee, Dan Fliegel, Dane Hamann, Anthony Opal, and C. Russell Price. It first appeared on Sharkforum and has been preserved here.

|

Brian Barker Biography

|

Brian Barker is the author of The Black Ocean (Southern Illinois University Press, 2011), winner of the Crab Orchard Open Competition, and of The Animal Gospels (Tupelo Press, 2006), winner of the Tupelo Press Editor's Prize. His awards include an Academy of American Poets Prize and the 2009 Campbell Corner Poetry Prize. He has earned degrees in Creative Writing and Literature from Virginia Commonwealth University, George Mason University, and the University of Houston. He is married to the poet Nicky Beer and teaches at the University of Colorado Denver, where he co-edits Copper Nickel. Read excerpts here and here.

|

Interview

|

In your book The Black Ocean, the opening poem "Dragging Canoe Vanishes from the Bear Pit into the Endless Clucking of the Gods" varies widely in line and form. How did this come about, and what were your intentions? Barker: This type of long poem in varied sections is a poem that I learned how to write from reading the work of Larry Levis. There are three such long poems in my first book, The Animal Gospels, and it felt like the right form for such a large subject matter--the genocide of the Cherokee people--that spanned hundreds of years. In a sectioned poem like this one, the white space allows you to shift gears, to move in time between sections, for example, or to switch points-of-view, or to slide between the lyric and narrative modes. When dealing with large subject matter, this method gives you the opportunity to layer images and to circle the subject matter, to try to get at it from different angles and bring complexity to the poem. Also, as a writer, I just find such shifts in style fun and challenging, and, pragmatically, a way to create texture that keeps a long poem like this lively and from becoming too dense and boring. Many of your poems have long titles, some of which seem humorous or ironic. Please discuss how you want the titles to function for readers. Barker: That's a good question. I often tell my students that titles need to do work for the poem--that they need to ground the reader and contextualize what's to come, in some way. I would argue that the long titles in the book do that, in a couple of different ways. The poems in The Black Ocean really push the boundaries of the imagination. They try to go as far out on the branch as they can before it breaks. I guess, in some ways, I was trying to do the same thing with the titles--to honor the aesthetic at work in the poems and to prepare the reader for what was to come, both in terms of the subject matter and the thrust of the imagination at work. I hope at the very least that they pique the reader's interest and entice them to keep reading. The Black Ocean has many surprising and original metaphors throughout, sometimes in rapid succession (such as in "Silent Montage with Late Reagan in Black and White," for example). a. Could you discuss your compositional process regarding simile and metaphor? Specifically, how much of the figurative language we see on the page arrived in first drafts, and how much was the result of revision? Were there any that you recall really laboring over? b. How do you see simile and metaphor functioning within your poems in The Black Ocean--what effects do you want to have upon readers? Barker: Oh, not much arrived in the first drafts, I don't think. It's hard for me to say, honestly, as the revision process begins for me the minute that I start writing. I work and rework lines and images and language from the get-go. (Interestingly, Kurt Vonnegut used to say that writers are either swoopers or bashers. Swoopers swoop through the first draft, never pausing, and then go back and revise extensively. Bashers rework each line or sentence or paragraph, step-by-step, as they go along. I'm a basher, no doubt.) I love similes and metaphors. They're the good stuff I go to poetry for as a reader, and I think that I'm a naturally visual poet, thinking and moving in images. I also believe that the making of poetry is a kind of serious play, even when you're butting up against dark or serious subject matter. I love the play of making metaphors, of yoking together unlike things to make something new. The best similes and metaphors are like connotative detonations. They're layered with emotion and thought and bring a deep complexity to a poem. That's the best I can hope for with my own. As I read The Black Ocean, I sensed a lot of "recent" news items within the lines (things like birds plummeting from the sky, etc.). I was wondering if that was intentional? I can see how the hyperbolic messages the mass media feeds us inferring "The End of the World" could go along with the messages in your book. I was also wondering where you get your news from? TV? Radio? Internet? FOX? ABC? NPR? Barker: Most of these poems were written between 2004 and 2008, and if you remember those good old times, there was a lot of bad shit going down. The war in Iraq and against terrorism, for one, which led to the Abu Ghraib scandal and America torturing its enemies, though no one would use the word "torture." And let's not forget Hurricane Katrina and the debacle of a response by our government. Then there's the acceleration of global warming that too many people in power ignored or scoffed at. Ultimately, I was trying to address a kind of culture of fear that it feels like we've been wading through on a daily basis since 9/11, and an administration in the Bush administration that used that fear to manipulate public opinion and the actions of its citizens. The apocalyptic narrative is a natural extension of that fear, it seems to me, and certainly all of this was, and is, exacerbated by the frenzy of the media. I try to get my news in bits and pieces, here and there. I can't take too much at one time these days; it's too oppressive and depressing. I read The New York Times, and listen to NPR when I'm in the car. There are a few other alternative news websites that I like. I rarely turn on the cable news networks, unless there is some huge event that's unfolding, and then I'm like everyone else, glued to the television. You have a rich and broad vocabulary, as made clear in the book; I was wondering if there were any words you tried to avoid using when writing a poem. Barker: Not really. The only language I try to avoid is the familiar and the cliché. As much of the book centers around historic events, I was wondering where you saw our modern day in the timeline? Are we just a blip on the radar, or are we at a unique and critical crossroads, like the Trail of Tears or Chernobyl. Barker: There are certain periods one lives through, it seems to me, which prove difficult to assess, in terms of significance, without distance. There are other times when it seems you can feel the pressure of the historical moment all around you. It's palpable. For me, the last ten or twelve years have been like that. I don't know if I would describe our contemporary historical moment as at a crossroads, but the burden of it certainly feels significant to me, and hard to ignore as a writer. Was there any particular reason for starting "The Black Ocean" with the poem that you did. Barker: "Dragging Canoe Vanishes from the Bear Pit into the Endless Clucking of the Gods" was the first poem I wrote after my first book, The Animal Gospels, was published. It's very similar to the long poems in that first book--a long, elastic lyric-narrative poem in sections that's composed at the intersection of the personal and the historical. It's a poem that mixes childhood memories of visiting Cherokee, NC with meditations on the violence inflicted on the Cherokee by the United States government. On the one hand, I put it first because it felt like a bridge from the first book to The Black Ocean, and in many ways it's different than a lot of the other poems in the book. Thus, it was hard for me to see where else it might logically fit if it didn't go first. On the other hand, though, I also see it as a poem that announces themes and concerns that many of the poems in The Black Ocean try to address. The early history of our burgeoning country is one shaped by our quest for natural resources and land at the expense of Native Americans. In this particular case, the Cherokee warrior Dragging Canoe decided to fight back by forming an alliance with other tribes. For years they attacked white settlements, indiscriminately killing men, women, and children. This is an early example of domestic terrorism, of the less powerful trying to find a way to fight back. I'm not an apologist for terrorists--far from it--but I do believe whole-heartedly that history can teach us something. Terrorism is often a response to particular American polices, now and at other times throughout our history. This hasn't changed. We have to pay attention to such things and try to learn from them. Obviously we haven't learned enough yet. How do you handle being married to another poet? Do you ever write together, in the same room, or do you keep your creative processes separate? How far along does a poem have to be before you show it to your wife? Are there any poems in The Black Ocean that you two didn't agree on - that she didn't like or didn't think should be included? Barker: Being married to another poet is a blast! First, poets are a weird breed. We work strange hours and brood a lot, and when we're deep in a poem, we can walk through the rest of our lives in a kind of daze. My wife, Nicky, understands this, being a poet herself, so there's never any need to explain or apologize. I also think that Nicky is my best reader. She knows what I'm after in my work, and when it's not on, she says so and doesn't beat around the bush. We have that kind of open exchange and aren't sensitive to such criticisms, which I think helps. We don't compose together. We each have our own studies, and when we write, we hole up in them in solitude. I think both of us hold back on drafts until they are either very close to being finished or until we come to some sort of impasse where we need the benefit of a fresh set of eyes. I'm wary of showing my work to anyone too early, as I feel the poem in early drafts is so malleable, I don't want the influence of another opinion or vision. I don't think there are any poems in The Black Ocean that she doesn't like. In early drafts of the manuscript, there were poems that she pointed out as being weaker, and she was right, and I eventually dumped them. She's a smart cookie; I usually heed her advice! Your poems are lyrical, though they don't often stray into rhyme. How do you see the sound functioning in your poetry? How important is the sound of a poem to you in general? Barker: I think two things drive a poem--image and music. A poem doesn't need to rhyme to be musical. Line and language alone create music, and poets need to pay attention to what's going on aurally as music in poetry is expressive. I read all of my poems out loud as I compose so that I can hear that music in the air. So it's a very important aspect to me, no doubt. Your work is obviously driven by the natural world - what poetic tradition do you see yourself interacting with? Who are your influences? Barker: I'm sure that there are both Romantic and Modern influences at work in my poems, but I don't usually think about interacting with any one poetic tradition. I do believe in influence, though, and embrace my influences openly. I can remember being in grad school when my teacher Mark Doty said that he didn't believe in the notion of finding one's voice. He believed that voice was something cobbled together out of other voices that have spoken to us. I found this incredibly liberating, and I see now how my own voice has developed in layers, and continues to develop, as I change as a person and as I find new writers that I love. Some of my influences include Walt Whitman, Federico Garcia Lorca, Czeslaw Milosz, Zbigniew Herbert, Charles Wright, Larry Levis, Philip Levine, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Judy Jordan, and Galway Kinnell, to name a few. The historic events mentioned in the poems in your book, The Black Ocean, come from several different eras. As a reader it's interesting to note how the poems relate to each other, such as the poem about the 1838 displacement of the Cherokees and the poem about the 1986 displacement of Eastern Europeans during the Chernobyl disaster. How did all of these poems come together? Do you think it's easier to write about long-past events or more recent ones? Barker: They came together fairly organically. I was first obsessed with current events--torture, Hurricane Katrina, etc.--and thinking about issues of power and acquiescence. This led me, naturally, to other historical events that spoke to our own historical moment that felt so big and uncertain. How I hit upon those other subjects was not very calculated. It often comes down to whatever gets its claws into you. For example, I'm a child of the Cold War, so I started thinking about all of those things from the 80s that are part of my own historical memory, and how they might speak to our present times. This led to some reading and research, which lead to the Gorbachev poem, and, then, eventually its companion poem about Reagan. In the end, I believe all we have as poets are our obsessions, and I try to be true to those and follow them wherever they lead me. Perhaps it's easier to write about events that are long past, as we have the long view of history to help us out. There's usually more heat to current events that we're personally wrapped up in some way, which can be a good thing or a bad thing, depending on how you handle it. In the notes to The Black Ocean, you write that several poems are indebted to photographs or paintings. Can you explain how you utilize the visual arts in your poetry? As a poet, do you believe it's important to bring many different sources, such as art and other media, into the creative process? Barker: I love ekphrastic poems and often teach them to my students. Strangely enough, though, I've never written a straight ekphrastic poem that's been worth a damn. However, I do often turn to painters and photographers for inspiration. It's just a way for me to get the creative juices flowing and to get below the surface of the real world and into the realm of the poem. Right now, for example, I'm working on some animal prose poems that have been influenced by the paintings of Walton Ford and Josh Keyes. You'd probably never know that from reading the poems, but the influence is there, just off-stage. I think each writer's creative process is discovered independently. Thus, I'm very wary of decreeing that every writer should do this or that. What works for one person may not work for another. With that said, though, I think visual art is a great stimulator, especially for those times when you might feel stuck or having trouble entering into the space of creation. Paintings and photographs activate the imagination and ask us to dream, as do good poems. Is there a specific era or decade that you find particularly fascinating and worthy of examination through the poetic lens? Barker: No, I don't really have an affinity with any particular era. I just follow my mind and imagination, and go wherever my obsessions lead me. One of my favorite poems in The Black Ocean is "Field Recording, Billie Holiday from the Far Edge of Heaven," could you describe your process for the creation of this poem? Barker: I'd been reading about Billie Holiday and listening to a lot of her music. I was interested in her as a marginalized figure--her banishment from the NYC club scene after a drug conviction, her harassment by the FBI, and all the flack she caught about "Strange Fruit." This ghostly voice lingering in the margins came to me, and because I had just finished writing the longer Hurricane Katrina poem, the drowned landscape of the city surfaced as the backdrop. Interestingly, the last image of that poem--the plummeting pelicans--was the final image of a love poem that I had written a few years back. I was never happy with that poem--a bit too sentimental. But I don't throw anything away. In the middle of writing that poem, I remembered that image and recycled it. That happens every once and awhile, which is why I save everything, even the miserable failures. What I loved most about reading your poems was the constant linguistic surprise I found line after line. How do such strange and beautiful words come into your poems so effortlessly? Do you have a way of collecting words you stumble on and love? How do you come across them? Cross-words? Simply reading? Barker: Thank you for the kind words. I'm glad it looks effortless; that's always the goal. But don't be fooled. I labor with language as with every other part of poems that I write. I love rich language. I love the texture of it and how it feels in the mouth. And I like discovering new words and widening the palette of my poems. I keep a word hoard, and whenever I come across a word that I love--usually from another writer--I put it in my hoard along with the definition. I used to keep these in a notebook, but I've know discovered a dictionary app on my phone that allows you to not only look up definitions, but save words into a favorites folder. When I'm writing, I'll often scroll through those words and see what hits me, what might fit. I also at other times will just read through the list and try to commit some of the words to memory. I've been known to read the dictionary on a Saturday night. If you're going to be a poet, you might as well go ahead and embrace your nerdiness! If you could only have three other poets to dinner, living, who would you have and what would you serve them? Barker: Oh, wow! Good question! I think I'd invite Ilya Kaminsky, Terrance Hayes, and Charles Wright. Ilya because he's the most sincerely passionate poet I've ever met. He gushes when he talks about poetry, and I'd love to have the opportunity to talk with him extensively about the poets he loves. Terrance, because I love his poems. I think he's one of the most inventive poets writing at the moment. And besides, he's one cool dude. Charles, because he's always been a touchstone poet for me. Not only one of the first contemporary poets I fell in love with, but a poet that grew up thirty minutes from where I grew up. That Appalachian landscape is in my blood, and I've always felt a deep connection to his work. |

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >