- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

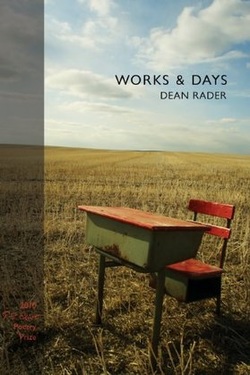

Interview with Dean Rader

This interview with Dean Rader about his collection Works & Days was conducted during the summer of 2011 by the following poets: Aaron Delee, Sarah Jenkins, C. Russell Price, Lana Rakhman, Christine Pacyk, Anthony Opal, Danielle Burhop, and Dane Hamann. It first appeared on Sharkforum and has been preserved here.

|

Dean Rader Biography

|

Dean Rader has published widely in the fields of poetry, American Indian studies, and popular culture. His debut collection of poems, Works & Days, won the 2010 T. S. Eliot Poetry Prize, was a finalist for the Bob Bush Memorial Award for a First Book of Poems, and it won the 2010 Writer's League of Texas Poetry Prize. In 2011, he was a finalist for the Poetry Society of America's Louis Hammer Award judged by David Lehman, and his poem "Self Portrait as Dido to Aeneas" was selected by Mark Doty for Best American Poetry, 2012. His most recent collection of poems, Landscape Portrait Figure Form (Omnidawn), was named by the Barnes & Noble Review as one of the Best Poetry Books of 2013. His newest collection of poems, Self-Portrait as Wikipedia Entry, is forthcoming from Copper Canyon Press in 2016.

|

Interview

|

When I first picked up your collection, before reading any of the poems, I made the connection between your title and Hesiod. In what ways did Hesiod's largely agrarian poetry influence this collection? Rader: I grew up in a farm town in Western Oklahoma. In fact, up until a couple of years ago, we still had a family farm, though neither my parents nor I worked the farm. But my grandfather did, as did his brother and, of course, their parents. Most of the economy in Western Oklahoma is farm-based, so I grew up smack dab in the middle of the culture, the patterns, and the values of farming. I was always very intrigued by Hesiod's Works & Days. It's a zany text. Rambly and a bit crazy. But, I loved how Hesiod's poem articulated this deep connection between farming, duty, and the divine. It was a trinity I related to on a profound level. That said, I was also fascinated by how Hesiod might react if he were magically dumped in the middle of the Dust Bowl. My grandparents were Dust Bowl survivors, and I think they never really got over it. I'm pretty sure Hesiod would have been astonished; thought the world was ending. He would hardly recognize that mode of farming. The machinery, even then, would freak him out. That's the genesis of "Hesiod in Oklahoma, 1934." "A Genealogy of Unfinished Love Poems" and several other poems include blanks, which leave the poems subject to the reader's interpretation more than if you had chosen to complete them. How and why did you come to this decision? Rader: I like elision. I like indeterminacy. And I like meeting (and gently frustrating) reader expectations--especially with love poems. In this piece, I wanted to write the most common kind of poem (a love poem) but also wanted to make it customizable. I really want the book to love the reader, and this is one way of making poetry more participatory. You can make aspects of the poem be what you want: funny, dark, sentimental, theological or even dirty. One time after a reading in LA, I overheard one woman telling her friend that they should go home open up some wine and fill in the blanks. That made me pretty happy. I noticed that the cover of your book was designed by your wife. Besides inspiration for an occasional poem, what role does she play in your work--editor, sounding board, muse? Rader: Hmmm . . . there seem to be so many ways to mess up this answer. My wife and I have a very collaborative relationship. We both do pretty much everything and share in everything. One thing that tends to remain our own is our work. She actually studied English and Russian at the University of Chicago, but she's not an academic. She works in the dot.com field. So, the details of our work don't overlap. However, I do show her poems, and the one thing she always urges me to do is to make them more accessible. Academics often have a tendency to write for themselves, to be intentionally obtuse or self-referential. She pushes me away from that. She would say the strength of the book is its ability to be accessed by many people. As for the cover, she has a great eye. I love the design work she did. The cover is both inviting and a tad spooky. On Anaphora & America: Your use of anaphora, particularly in "Self Portrait: Rejected Pop Song," is striking, because the repeated phrases do not only frame and heighten the language, but they also steer the poem into commentary: it starts to read like a tiny jeremiad, a list of societal ills delivered with some wry nonsense-type humor ( ex: Just tell me you're the mouse ears/ Just tell me you're the asschord, the asschord ) with a complete drop-off at the end ( We are the logos, the logos/ We are this the ). You choose to echo Eliot's Wasteland in this poem (shantih), as well as Eliot's use of allusions of high- and low-brow nature throughout (ex: "logos" can be read both as the high Greek "reason," or the "low," American circa 1950s modernist "logo"; see: Nike, Coke). Your content and type of humor here strikes me as quite American - a nod to the silly ( ex: No one is the White House homeslice ) as a means of getting across some cutting barbs. Rader: Another smart observation. I would add to your good reading that this strategy is particularly Oklahoman. Eliot's poetry, especially the close of Wasteland can be so . . . precious, so high modernist, so neo-holy, I wanted to play with that a little. The translation of that appears later in "Frog Seeks Help with Anger Management," which again, tries to (mis)align high and popular culture. The poem seems to be commenting on something, and I think it might be more than the idea of a pop song as a frame for identity. I'd like to hear what your inspiration was for the poem, and how it developed for you - and whether you think my assessment is fair, to classify this as an "American" poem, in the sense that it seems to orbit around and comment on familiar American tropes. Rader: Yes. I wanted to do a few different things with this poem. One, I wanted to write a poem with anaphora that also took advantage of parataxis. Two, I wanted to play with the ability of pop songs to be both ridiculous and socially relevant. I'm always astonished how eager musicians, fans, and critics are to endow pop music with the mantle of social commentary. If a song can be both, certainly a poem can. And lastly, as you astutely notice, I wanted it to be a tad unclear if the poem is earnest or funny, deep or goofy, an homage to pop or a parody of pop. And lastly, I hoped the poem would become part of this larger conversation in the book about identity and the self as being formed in conversation with another text or texts. On Humor: Mark Twain said: "There are several kinds of stories, but only one difficult kind--the humorous...The humorous story is American, the comic story is English, the witty story is French. The humorous story depends for its effect upon the manner of the telling; the comic story and the witty story upon the matter. The humorous story may be spun out to great length, and may wander around as much as it pleases, and arrive nowhere in particular; but the comic and witty stories must be brief and end with a point. The humorous story bubbles gently along, the others burst." I am a big believer in using humor in poetry, for its ability to subvert the obvious, but also for its ability to surprise, and introduce discomfort. I noticed that you laced Works & Days with humor, particularly re: Frog and Toad: ( Hey, Frog exclaims, God and Toad sort of rhyme! ) and I was hoping you'd talk for a bit about how you think of humor in poetry, and what you hope it adds to the texture of your own work - and whether you agree with Twain's assessment, that there is something American about using form as the vector for humor. (I realize Twain referred more to narrative text, but I think his assessment of how "humorous stories" develop will have resonance for poets; please feel free to disagree.) Rader: Great question. I wonder, in reading Twain's quote, if the distinctions between witty, comic, and humorous have softened over time. Works & Days has been called all three by reviewers and maybe even by blurbists. How grand that I may be embracing my inner Frenchman. I do think there is something American about the willingness not to be taken seriously. Or, better phrased, I think we are more eager than most to be seen as not taking ourselves or the world too seriously. We are willing to be unpolished and even ridiculous and to be knowingly, intentionally so. Perhaps it's part of America's ontology--our identity as rebels, revolutionaries, outlaws. As for poetry, I like it when humor can puncture the puffed-up pretentiousness of the lyric. But, I also like it when humor becomes a form of insight and revelation. To note the comic in the everyday is to be the most human. So, I love it when poems acknowledge and embody that. I should say that I've never been a fan of the Theater of the Absurd, and I tend not to respond to absurdist texts. Another confession: I don't like stand-up comedy. It almost never makes me laugh. What does make me laugh is the willingness to be vulnerable through humor. And to be wise. Also, humor, along with grief, is the great unifier. It disarms. It invites. It's hospitable. On Construction: In a number of your poems, you do not "hide the seams," but instead allow the reader to see the construction of the artifact (ex: "PowerPoint Presentation on the Sonnet"; "A Genealogy of Unfinished Love Poems"). Some of your use of figurative language had echoes of this method to me as well; for example, in your book's very first poem, you hit the reader with two instances of bold figurative language straight away: The leaves leave on their orange parkas. / Winter sidles up like a bad salesman. You do something similar in the next poem, "Frog and Toad Confront the Alterity of Otherness": The sun was hot in the sky/ like a muffin in a bright blue tin. These are not sly metaphors that sneak up on the reader at the end of a poem, to sort of stand in as wise denouement; these start the poems in question, and call attention to themselves. I'd argue that they aren't quiet metaphors - and that, like your visually constructed poems, you intend for the reader to notice that these descriptions and comparisons are created. If you do have a particular take on figurative language, I'd love to hear more about it. Rader: That's such a smart observation. I don't know that I could articulate it any better myself. You've said almost exactly what I would say. As part of my minor project to make poetry less pretentious, less anxiety provoking and, to a certain degree more populist, I am interested in debunking the myth of the precious genius, the artfully made jewel box, the glorious flawless product of divine inspiration. I believe that poems are made. Like crops, they flourish only out of hard work and a little luck. So, I like leaving the tractor in the field, the plow outside the furrow. It is a remnant of where the human hand was and is. I sense the influence of Charles Wright in some of your poems. What poetic tradition, if any, do you most identify with? Rader: As far as contemporary American poets go, I think I'm most jealous of Charles Wright, Terrance Hayes, and Jorie Graham. Wright in particular. I love his cadence, his crazy images that are always just a bit off, and his easy manner of making complex ideas go down like iced tea. Like Wallace Stevens, he a master of tonal modulation. He can write the most beautiful lyric line then follow it up with some smart-ass southern pith. And, obviously, two of his major concerns--language and the idea of god--also concern me. I would say I most identify with poets who look to the poem as a language-based way to make sense of the world. I'm more interested in language than story or narrative, but perhaps paradoxically, I am also attracted to poetry whose innovative language is not overly distancing. I like some L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry, but it doesn't move me; same with flarf. I will be more likely to skew toward all of the poets I mention above, plus people like Rilke, Celan, Akhmatova, and Amichai on one spectrum and folks like Bob Hicok, Lucia Perillo, and Troy Jollimore on another. Your forms vary. Some of your poems are more traditionally left justified, while others sprawl across the page. What makes a poem need to spread out? Rader: If a poem wants to expand or to be expansive, then it tells me it wants to stretch. Or, alternately, if a poem tends to be about the line, about the isolation of the line, then spreading and staggering lines can make things stand out. Other times, I want the reader to experience a feeling of descent, so the poem deescalates. Other times, I want a poem to be as much about silence or breath as about noise or words. And spreading out the poem can balance negative and positive space and cadence. In the third part of the book, "Days," you encompass almost a decade of time in as many poems. How did you go about writing poems that take place over such a long period of time? Were there other poems for important dates between the years that we see now, or even duplicate poems for some of the years, that didn't make it into this book? Was the numbering of the Days poems conceived of as the poems were being written, or did that come as you were assembling the manuscript? Rader: That's a frequent question. Folks are surprised I might have been working on a project for 11+ years. But, it's true. Except for one or two, each of the poems was written if not on my birthday then around the respective birthday (with the exception of "Ocean Beach at Twilight: 14"). I was interested in a kind of map of what I was doing or thinking about or reading at these moments when I moved into another year. A poetic calendar of sorts. So yes, the numbering was intentional, and embarrassingly, planned for a l-o-n-g time. Some of the poems were published without that date attached to them, but others were published with the dates as part of the title. I don't think there are other occasional poems in the book, except the opening poem about my grandmother's funeral. The Cuba poem I started while in Cuba but finished after arriving back in the states. Oh, that Yeats poem. I started a version of that on the day of the new millennium, but that poem swerved rather dramatically. There are several poems in this book, most notably "A Geneology of Unfinished Love Poems" and "[ ]," that utilize an underlined blank space. Did you incorporate the blanks as you were writing your poems or did you finish the poems and then return to them and remove certain words? Do you think the blanks open up the poems more for the readers, or was there a different intention? Rader: The original version of this poem was written for a wedding celebration and had no blanks. But, the poem needed a makeover to move from a celebratory performance to a poem that could stand on its own in a journal or book. I thought the poem in its original form participated too fully in the convention of the occasional love poem. I wanted a way to, as you say, open up the poem, and to let the reader know that I believe in her. Besides the underlined blank spaces, there are several other elements in your poems: various bullets and symbols, a division symbol (Curiously, one name for this symbol is "obelus," which was used by ancient editors to mark passages in text they believed to be untruthful. Is there a double meaning here?), brackets, and strikethroughs. These elements are used sparingly but prominently, yet probably can't be considered a thematic style. Can you explain why you used them? Rader: Again, I like showing the printer's marks, the seams, the stitches, the boom mike, the blooper, the edits, and, in some instances, the options. In poems with strikethroughs and brackets, I'm hoping to indicate that the poem could have gone in a different direction or, depending on how a reader reads the poem, can now go in a different direction. For me, a poem is never fixed. It never has only one way of getting to the end. I'm so happy you know the printmaking history of obelus. The dash, the division sign--they are all connected. And, yes . . . The frog and toad poems are particularly compelling; where do they stem from? What inspired you to write about them? And, do they have a personal connection? Rader: When I was moving from one place to another in San Francisco, I came across my original copy of Frog and Toad are Friends, a book I loved as a tike. It's one of the few children's books I actually remember (along with The Pokey Little Puppy). I was tired that day, so I just sat down and read the book all the way through. There was one story in particular that fascinated me. Frog wants Toad to tell him a story, but Toad can't think of one. He tries all these tricks--going for a walk, pouring water on his head, banging his head against a wall. But the story won't come. Finally, the story comes and it goes something like this: Once upon a time there was a Toad, and his friend Frog wanted to hear a story. But, he couldn't think of one so he poured water on his head, banged his head against a wall. . . I thought that was so smart--creative, self-reflexive, postmodern, funny, sort of strange, and just sweet. I remember thinking someone should write a poem about Frog and Toad. A few days later, it occurred to me that that person should be me. So, I started working on "Frog and Toad Confront the Alterity of Otherness." I wanted to do in that poem what I want the whole book to do--blend high and popular culture. I wanted a sophisticated mash-up that would just toe the line between being provocative intellectual and wholly accessible. Smashing poststructural theories into characters from a children's book seemed like it might yield some fun (and thoughtful) poetry. Aside from frog and toad, you also undertake a number of Self Portrait poems; what attracts you to the self-portrait, and how do you approach it? Do you have any rules/guidelines when composing a self-portrait? Rader: In general, I only like self-portrait poems that are not overtly about the self. One of the epigraphs of the book comes from the scientist Kathy Steele, who, rather matter-of-factly states that the self is not continuous. I love this notion that the self is never fixed--like a poem--is always being composed and revised. It's also increasingly clear that identity is formed through relation; so rather than write a standard autobiographical poem or a predictable confessional poem, I am more interested in suggesting how the self (or selves) is collaged via that which is not the self; that is, how the self is constructed through poems, art, music, philosophy, science, family, politics, etc. Your poetry is very verbose; you've got a breadth of vocabulary at play in your poems (which is much appreciated by this reader); I was wondering if you had any words that you tried to avoid when writing, or that just tend to rub you the wrong way; and if so, why? Rader: Yikes! When I read the word "verbose," I panicked. I tend to have negative associations with that word (pompous, rambly, fatuous). One of my fears is that too often, the poems contain words that might turn off some readers. Alterity, alethia, metonym, antinomy. My parents were just totally stumped. The book has gotten good reviews--I've been very lucky--but the one sort of negative comment was that the middle part of the book is marred by "postmodern pastiche." I don't agree, but I do worry that whatever the reviewer saw in this part is somehow linked to an insider vocabulary. My poet eye and ear is okay with this; my Oklahoma farm boy roots are not. As for words I avoided . . . I wanted to be wary of "love." And I hoped to avoid the word "nature." I also wanted to avoid words I kept seeing in contemporary poetry like "calyx." I also tried not to use introductory phrases of setting like "Today, while walking . . ." or "This morning, I noticed . . ." My friend Matthew Zapruder does that well. I do not. You use the Spanish language sporadically in your book. In certain poems, I was pleasantly surprised by this switch (like in the Frog and Toad poem), but in other poems Spanish seemed to emerge organically. Can you outline your process by which you chose when to insert Spanish, and why you insert it; also, why Spanish, versus another language? Rader: I love Spanish. I think it is the great language for poetry. I wish I could write a whole poem in Spanish. I like it sonically, I like it semiotically, and I like it syntactically. Plus, it reminds me of Neruda and Lorca. Though, when I do the poems out loud at readings, I am embarrassed by my oh-so-lame pronunciation. I think I use Latin as much if not more than Spanish. My use there is obvious, I assume. It's the language of the church, of formality, and of learning. I like inserting Latin phrases into non-Latinate settings to, again, create what I hope is both humorous and enlightening juxtapositions on culture and language. How did the title of the book come about, and how do you deal with titles in general? I noticed that all of your poems had terrific titles, and I would like to know more about this process; do you title a poem after it is written, before, during, etc. Rader: Great question. As you no doubt intuit, I'm obsessed with titles. I learned this from Stevens who is the master of the misleading-yet-not-misleading title. James Wright was also good at this. I am a picky reader of poems. I assume if I am not drawn in by the title that I won't respond to the poem. So, I want the poem to entice the reader. Also, I think a poet can get away with a slightly more oblique poem if s/he uses a funny and/or helpful title. In general, the titles come after the poem. I think of the title as being in conversation with the poem. The title and the poem complete the incompleteness of the other. I know there were a lot of questions about the blanks that appear most prominently in "A Geneology of Unfinished Love Poems," but also in "Self Portrait: Rejected Pop Song," "[ ]," and "What This Is: 35." While those questions focused on author's intent, I'm curious as to how Rader intends for, or simply hopes, the reader will navigate them--when he reads them, does he use the word "blank," or pause? There is an invitation for the reader to "complete" the line by filling the blank, almost a poetic Mad Libs. (It's another opportunity to talk about the blanks, from the reader's perspective.) Rader: I was just asked this very question at a reading. One audience member, also a poet, asked why, during a reading, I say the word "blank" rather than simply pause in silence. I had never thought of this, in part because there is not a blank space there, but a line. There is a mark, a textual symbol. To me, that indicates something rather than nothing. I'm glad you see the Mad Lib connection. I've actually admitted that I missed a fun title opportunity here. My hope is that the reader will first see the blank and see/read "blank" but then wonder what I might have intended before ultimately putting in the word the reader wants to see there. It's all about the fulfillment of desire! There are many nods to poets who have influenced/informed your writing: Hesiod, Wallace Stevens, Charles Wright. How has your work in American Indian studies influenced your poetry? Rader: That's a tough question. Perhaps the recurrent theme of identity has influenced me. Perhaps also the tendency to play with form and genre. I guess I'm resisting answering the question because I don't want to make sweeping generalizations about "Native American Poetry." I can, though, see some commonalities with specific poets. Like Sherman Alexie, I tend to like funny poems; like LeAnne Howe, I enjoy tinkering with form; like Sherwin Bitsui and Orlando White I'm intrigued by language on a syntactic and semiotic level; like Linda Hogan, I am attracted to individual lines of beauty. Your poems have a biting realness to them, do many stem from personal experience? I'm specifically thinking of "How to Buy a Gun in Havana," and how that poem came about? Rader: That poem came about after a long afternoon my wife and I spent with a local couple in Havana. Most of the details in the poem come from that day. They took us around to some bodegas and explained how things worked. I knew I really wanted to write a poem about the experience, but I did not wanted to be exploitive. So, I went sort of . . . noir. But, the narrative arc of the poem was largely influenced by the Cuban American novelist Cristina Garcia, who is a good friend. For over a year, she and I exchanged a poem a month. I was always impressed by how her poems had little plots. They told stories. I wanted this poem to be a slight departure for me. I wanted to write a story poem. For one poem in the book, I wanted story to overtake line, language, structure. If you could drive cross-country with any three poets, who would you pick? And who would you let choose the music? Rader: Would we all be in the same car? Dear god . . . That's an impossible question, but I'd pick Terrance Hayes, Bob Hicok, and, of course, Simone Muench. Hayes gets to select the restaurants, Hicok the route, and Muench the alcohol. |

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >