- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

Interview with Hadara Bar-Nadav

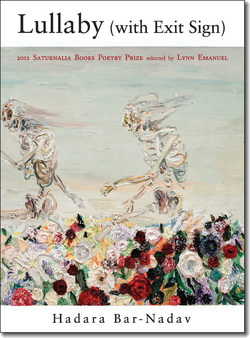

This interview with Hadara Bar-Nadav about her collections Lullaby (with Exit Sign) and The Frame Called Ruin was conducted during the summer of 2013 by the following poets: Jim Davis, Dan Fliegel, Adam Lizakowski, Anthony Opal, and C. Russell Price.

|

Hadara Bar-Nadav Biography

|

Hadara Bar-Nadav is the author of Lullaby (with Exit Sign), awarded the Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize; The Frame Called Ruin, Runner Up for the Green Rose Prize; and A Glass of Milk to Kiss Goodnight, awarded the Margie Book Prize. She is also the author of two chapbooks, Fountain and Furnace, awarded the Sunken Garden Prize, and Show Me Yours, awarded the Midwest Poets Series Prize. In addition, she is co-author of the best-selling textbook Writing Poems, 8th ed. Recent awards include the Lynda Hull Memorial Poetry Prize from Crazyhorse and fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She is currently Associate Professor of English at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

|

Interview

|

Many of the pieces in Lullaby (with Exit Sign) are prose poems. Could you discuss your process regarding prose poems? For instance, do you consciously set out to write a poem without line breaks, or do you take a draft and then “stretch” it into the prose form—or both of these? Furthermore, what do you believe is lost, gained, or changed by writing and/or reading a poem that is in a prose format, specifically with the elimination of the “poetic line”/line break? Finally, many of your prose poems make use of many sentence fragments, such as, for example, in “To Ache Is Human,” where your write, among others lines, “The nerve in nervous, in sever and serve.” How do you use fragments to affect the rhythm or caesura in your prose poems?

Bar-Nadav: The poems in Lullaby (with Exit Sign) are largely elegiac. I don’t know that I initially decided to write a manuscript of prose poems. The weight of grief just leveled me, and leveled the poems in terms of form. Once I started to write a few of the Dickinson-inspired prose poems, I discovered I had a form to lean on, and this helped me as I navigated the writing of these (often difficult) elegies. I don’t think anything is lost in writing prose poems, except for, obviously, the line break. But the line break could be said to be “ghosted” in other ways; pauses become suggested through syntax and sound. The hard syntax and sound of the prose poems in Lullaby would have been too obvious, in my mind, broken into lines with neat end-rhymes. Nothing is neat about grief. It is messy and consuming, coming from all sides at once. The syntax and sound was thereby cast in tension against its form, which was a formal way of creating even more tension. The way I use fragments is probably specific to each poem—each soundscape that arose as I was writing each poem. But I was very aware that many of these poems would need fragments—language at the breaking (or already broken) point. Many of these poems felt ripped through my teeth. I didn’t necessarily want to write them (just as I didn’t want my father to be dead). But I also knew I had to write them, for my family, for myself, and most importantly for other people, those readers who have suffered grief and loss. The poems helped me overcome the smothering silences that often surround grief. Ask someone whose family was killed in the Holocaust what silence is—large as an ocean, as the sky. One of my favorite poems from Lullaby (with Exit Sign) is “Prayer Is The Little Implement.” This poem seems to deal explicitly with the limits of language, comparing and contrasting words (“Each grain, each letter, another meager little”) with “The meaningless hum of rain.” In two parts of the poem the words “fall” and “fail” appear next to each other (“…fall. Fail.”), and at the beginning of the poem and in many other poems in both books you use alliteration, assonance or consonance to make unexpected juxtapositions or turns (“Tool or tooth,” “glass…gauze…gaze,” “burned…blind,” “flies and violins”). What are your thoughts about allowing the sounds of words to lead the sense—letting the music carry the poem where it will? Bar-Nadav: I especially enjoy pushing sound in prose poetry. When I read the work of someone like Karen Volkman or Simone Muench, I see how the prose poem can create opportunities for very visceral treatment of alliteration, assonance, and consonance, and rhyme and off-rhyme. I’m also a great believer in allowing the poem to go where it may, and, as you noted, sound was a major compositional device in the writing of these poems. At the same time, sound also enabled me to revise these poems, which I said aloud dozens of time as I revised. All this to say, sound can be both a compositional device and a tool for revision. Alice Notley once said to me that she revised through her ear, and her comment rang especially true for me in writing these poems. The insistence on voice and sound in these poems also made sense to me as I was exploring the elegy—in some ways I was exploring the cry in language and its many reverberations. The erasure poem you created from Emily Dickinson’s letters is very effective. Please discuss any new appreciation or understanding you have of her work (in diction, sound, line, or other areas) after that process piece and after referencing her poetry in your own poems and with many of the titles. Bar-Nadav: Dickinson’s poetry has a wonderfully strange and rich music, and her syntax is often surprising and fresh to me. It is timeless. It sings through pain, suffering, loss. It sings because of, in spite of, along with, before, and after loss. She taught me that I could write through grief, by example. I borrowed phrases from Dickinson’s poems for my titles and then imbedded a phrase from her poetry within each of my own poems. This method of collaboration not only helped me find a way to begin writing these elegiac poems, but helped me to continue. The erasure poem “Master (Pieces)” revealed to me that Dickinson was a poet through and through—that even her so-called letters were creative works in their own right. Her Master Letters—letters to an unnamed Master—also served as a kind of parallel to the elegiac poems I was writing, in conversation with my father, my family, the spirit world, and with personal and public history. In both books, the word “blood” appears many times, along with some related words (e.g., “clot”). Please discuss this as a recurring interest or motif, along with others that you see across the collections. Bar-Nadav: The Frame Called Ruin uses architecture as well as visual art as its primary metaphors to examine human frailty and power. Two- and three-dimensional works by Buckminster Fuller, Zaha Hadid, Louise Nevelson, and others become inspiration for poems that explore the impulse to create in a world that constantly destroys and renews itself. Construction and destruction coexist as do desire and violence. Blood is present in both destruction (death) and renewal (birth), and it connects people to one another. In Lullaby, blood is also the element that ties me to my family—my father, my mother, and my family members killed in the Holocaust. And it also the blood-jet, what keeps me alive and writing. Inherently, it can serve as a symbol of both destruction and creation, paradoxical impulses that have fueled my imagination for many years. I noticed in the notes for A Frame Called Ruin that some of the poems appeared in your chapbook. Could you discuss your process for compiling a chapbook—do you make it a “complete project” unto itself or do you use it as a shorter sampling of your work? On that same level, do you alter poems greatly to make them work within a “chapbook frame” then interject them into a fuller manuscript or did the poems change greatly between the two publications? Bar-Nadav: My chapbook, Show Me Yours, came early in the writing of the book manuscript The Frame Called Ruin. That is, I knew I had at least a chapbook of poems that I could organize into a coherent manuscript and strongly suspected that I could expand the manuscript into a book project. That being said, I know other writers who think of chapbooks as their own unique projects—not as works that will be expanded into a book manuscript. In the end, I think it’s writer and manuscript-specific—the poems ideally can tell you how they want to be in the world. I didn’t set out to alter/revise the poems because they were in a chapbook or book manuscript (although poems can speak to each other in various ways depending on which they are next to in a manuscript and that can influence the revision process). I actually had 26 versions of The Frame Called Ruin—I revised those poems and that manuscript many, many times. I’m a compulsive reviser. When I read new books (or even old books for that matter) I gain new insights, so it makes sense to me that I see things in my own poems that I didn’t notice before. But eventually, I realize I need to stop—and write more poems! My copy of Lullaby (with Exit Sign) is dog-eared beyond belief and looking back at the numerous poems I picked as my “favorites” I found that they all shared a heartbreaking similarity of combining the deeply natural with a strong personal emotion—such as the line from “To Ache is Human” which had my jaw-dropped for days, “A sunset without beauty.” Could you talk a bit about your fascination of combining the ethereal with sometimes the bitterly dark? There seems to be a fascination with unsettling the reader or skewing the image in some way—can you talk about this in your writing? Another example from the poem “I Would Have Starved a Gnat,” “Turning iridescent. Turning black. The kingdom of the body blown to ash. Buttons of us left in the sun. The crown and teeth. The aftermath. No moist benevolent thing between us. Take me. Take half.” Bar-Nadav: Dickinson’s inclusion of the natural world leaked into my poems. But I also found some solace in writing about nature, and, as you note in your question, nature served as both juxtaposition and metaphor. We return to dust. Nature comes to take us back in the end. Couldn’t death and the earth itself be a kind of home to the body and spirit? The poems “The Landscape Listens” and “Death is a Dialogue” engage this possibility. On the craft side, I think many if not most good poems contain tension, something unresolved and/or uneasy that haunts us and makes us want to return to the poem again and again. Through the pairing of nature and grief, dark and light, or through presenting a variety of tones, poems can contain many layers that draw the reader in. How do the Dickinson lines find their way into the poem – are they the seed from which the poem sprouts? purely ekphrastic? or do the lines serve as scaffolding, supporting the poem already on its way? Bar-Nadav: I stopped writing for several months after my father’s death. I then happened to start reading Dickinson’s poetry and basically gave myself an exercise to try to jumpstart my writing. I would use one of her titles to start a poem. And when I got stuck a few lines later or last faith in writing at all, I would insert another quote from her poetry. So yes, Dickinson’s lines served as both scaffolding and support—very kind and steady and necessary support. Did you know when you started working on Lullaby (with Exit Sign) that the project would center around Emily Dickinson? What was your impetus for starting this book? Are there other artists/writers that you admire that you’d like to explore in future work? Bar-Nadav: I began writing Lullaby one poem at a time, with no idea it would be a book. After I wrote a dozen or so of these Dickinson-inspired poems, it occurred to me that I might have a chapbook, a book, or even a section of a book. These poems were difficult to write, but also necessary. There is too much silence around death, too much fear. And it’s something we will all have to face. Artists and writers are a constant source of inspiration (I often surround myself with books of art and poetry when I write). I have thought about exploring the writing of Paul Celan as source material (I’ve previously experimented with some erasures of his work). I’ve also returned again and again to the visual artists Francis Bacon and Magritte. There is an interesting lyricism weaving its way through much of your work – what influence does sound have on your message? Does lyricism propel the poem and/or its motifs? If so, how do you coral yourself/not stray too far from the core? Bar-Nadav: If you are talking about lyricism in terms of sound, my response to question 2 (above) speaks to the issue of sound as a compositional and revision(al) device. Sound enlivens poetry. It tells readers viscerally and intimately that a voice or many voices are speaking. It asks to be listened to. I suppose the poet needs to try and balance sound and sense within each poem. That being said, the balance can tip one way or another for strategic affect. In Lullaby, I didn’t need to explain again and again that my father had died or that my mother had cancer or that I had family members who were murdered in the Holocaust in every poem. I don’t think of Lullaby as a book of narrative poems. I knew the poems collectively would hint at these stories, and so let the other elements of poetry rise: tone, imagery, metaphor, form, sound, disjunction, etc. For me, narrative wasn’t the way to tell these stories. Grief is, indeed, messy. How do you arrive at the decision to shift from prose poetry (p.32) to line breaks (p.33)? Do you enter a poem with form in mind or is that something that must be sorted out as the poem progresses. I am particularly interested in Suspension (p.45), where the form conjures haiku, although the subject and images are intensely wrought – pockets of macabre wonder “suspended” and descending down the page until it is “Fixed.” – a far cry from prose-form. Does a poem find its form as you write it, or did you decide, for instance, that a poem like "Let Us Chant It Softly" will be a prose poem before you start? How about a poem like Donor (Wind)? Also, without lineation, what poetic devices do you find driving your prose poems? Bar-Nadav: I wrote the lineated poems while writing the prose poems, and they surprised as my writing had been dominated by the prose poem. But poems like “Lullaby (with Exit Sign),” “Family of Strangers,” and “Lamb” seemed to need white space. Their haunting of the page needed to be visually represented/manifested through short lines and/or staggered lines. And the monostichs in poems such as “Blind Fragment” and “Donor (Wind)” asked to be ghosted across the page in a different way. The question of whether a poem finds its form as it is being written or if the form is dictated ahead of time largely depends on the poem itself. But there came a time in writing Lullaby when the poems that borrowed lines from Dickinson all came out as prose poems, and the poems that did not directly riff off her language became lineated. An early reader has suggested I lineate the prose poems—he thought the music leant itself to lines, but I disagreed. I also asked myself if this manuscript should only be made up of the Dickinson-inspired prose poems, but in the end decided that the mix of the two was a way of creating an essential variety and tension. Physically speaking, Lullaby (with Exit Sign) and The Frame Called Ruin are such different objects. What sort of input did you have on the design of these books? How do you feel that the object of the book effects the poems within it? What about something like online publishing, in which the physical object of the book is completely absent? Bar-Nadav: In The Frame Called Ruin, I was asked by the publisher New Issues to fill out a questionnaire to give to the book designer, which included a description of the book and a list of themes and inspirations. I also included art that had inspired the poems and other images that I thought could work for the cover. The designer then took all that text and imagery and created the current cover. With Lullaby (with Exit Sign), Saturnalia Books offered to let me to choose my own cover art, and I worked with Richard Every, a fantastic graphic designer. I requested the oversized format of The Frame Called Ruin, which I thought would allow the long prose poem sequences to breathe and engage white space. The size also somehow seems architectural, and suits the poems. The poems in Lullaby tend to be more spare, and the manuscript is shorter and more intimate. I think the small size, which my publisher chose (and I believe is fairly standard for Saturnalia Books), fits the intimate subject matter. Your very colorful cover of the book Lullaby (with Exit Sign) has two skeletons (symbol of death) walking across a very beautiful garden of roses, which could be a symbol of life. So how does your cover correspond with the themes of your poems in your book? Bar-Nadav: That gorgeous painting “Skipping Skeletons” is by the contemporary artist Allison Schulnik. It seems to insist on the vibrancy of the afterlife. Two skeletons skip through a glorious field of flowers. In person, the flowers in the lower half of the painting rise inches off the canvas, like dozens of smashed cakes with endless layers of rainbow-colored frosting. You can almost taste it—and are afraid to. The painting suggests the possibility that death or the afterlife could be vibrantly energetic, even ebullient. (Death is literally skipping!) In writing Lullaby, I called upon the dead, who also called on me, and learned (thankfully, mercifully) that energy and creativity can be experienced even in the midst of death. The spirit world is very much alive to me—my ancestors are with me still. In many poems in this book you mention a lot of human body parts. For example in the poem “Split the Lark” you mention eyes. In the poem “Dust Is the Secret” you mention face, fingers, and heart. How are the human body and its parts important for your poetry? Bar-Nadav: My mentor Hilda Raz once said to me that all art comes from the body. And this idea has stayed with me. Sensory experience is the vehicle through which we engage with the world, so the body for me is an organic and even necessary part of poem making (and how can we forget the breath--the breath!). In several poems in Lullaby (with Exit Sign), I was specifically contemplating mortality and the failure of the human body (in addition to ghosts and the voices of the dead). In The Frame, I was also exploring the human body alongside other structures, namely art and architecture. Interestingly, the terminology of buildings often uses terms from the human body (eg, “skin” refers to a building’s surface; a “head” refers to the upper horizontal part of a window frame, etc.). The tone of your poems is often sad, sometimes even dramatic and dark with a lot of human pain and despair. Some of the titles of you poems are pessimistic, for example “To Ache is Human”, “Darkness Intersects Her Face,” “I Don’t Like Paradise” or “Split the Lark.” There is blank verse with long lines, and dark elegies that are not always easy to understand. What is your inspiration for poetry that often delves into depressing subjects, and how does your form affect the tone? Bar-Nadav: The titles of the poems that you mention above are actually quoted from Emily Dickinson, who inspired me to explore the elegy (along with the death of my father). Of course, poetry knows no bounds. The entire spectrum of experience and imagination must be available for making art. I don’t see these poems as necessarily depressing. In fact, making art and writing poems is the most life-affirming and positive thing I can do with this material. Dark and light are necessary counterbalances in the world. And “dark” subjects don’t need to be surrounded by more silence. As a poet, my job is to articulate even the most difficult or painful things. Can you tell us about your current projects? Bar-Nadav: I’m currently working on two different manuscripts of poetry. One explores the interior lives of objects (ala Stein, Ponge, and the contemporary poet Ales Steger). The other project explores zombies, pharmaceuticals, and the dreamlife. I have also considered writing a memoir, though this is just a glimmer of an idea way off in the future. |

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >