- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

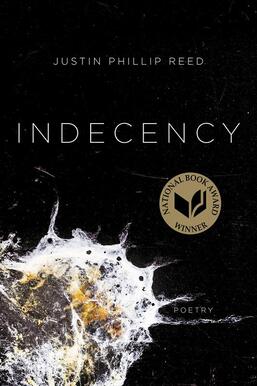

Book Review: Indecency by Justin Phillip Reed

|

Review

|

A Review of Justin Phillip Reed's Indecency

Justin Phillip Reed sutures language, “smudged reflections, / [and] histories flattened” in Indecency, a collection of scathing testimonies that demonstrate what it means to be a Black, queer individual navigating through heteronormative, white constructs. Reed is unapologetic in his examinations of how the Black body is a subject of racial and sexual violence, forcing us to “carry the carnal weight” that devastates the marginalized time and time again. In “Witness to the Woman I Am Not,” Reed gives voice to objectified women as an act of solidarity and unravels how they are engulfed in figurative and literal white spaces after introducing each passage with “(in which all this white is my gaze).” Following this recurring parenthetical is a series of black text blanketed in the whiteness of the page, almost swallowing “the labial-lingual demand of speech” to the point of erasure. The speaker deconstructs the woman further as the piece progresses, referring to her as “shorty” in the first passage, to “‘and she’” and “‘of her,’” to “‘snatched’ and ‘muffled’”—but, by the conclusion, the woman becomes a metonym: a “dress, a worried mess of splinters, somehow yet a dress.’” Reed then leads us to a morgue, where we become a witness to “missing Black girls” swathed in a “body bag somewhere” in “Pushing up onto its elbows, the fable lifts itself into fact.” There is no room for discomfort as Reed depicts the devastating reality of the “disposability of Black girls who are prone to disappearance,” and how “Outrage, too, has a way of being disappeared.” We are left haunted by the ghosts of abducted Black women underneath these white sheets, waiting to mourn another Black girl to go missing only to repeat the cycle of them turning into a statistic. Women are also othered and dehumanized by the patriarchal society they reside in, and Reed highlights this feminist lens before transitioning to the queer perspective in “Performing a Warped Masculinity en Route to the Metro,” “Take It Out of the Boy,” “Any Unkindness,” and “Exchange,” among others. These interconnected poems confront gender performativity, which is showcased through the speakers confessing that they are “tired / of pretending” to be a gay, closeted lover in “Take It Out of the Boy” and later admitting how “the mind threads the sting into memory” in “Exchange.” The blurring between masculinity and femininity is seen through the speaker’s connection with the sister and mother as figures who invoke “a synonymy: to protect and to devour.” This dichotomous relationship of both safeguarding his femininity and becoming emasculated is an internal struggle the speaker attempts to fathom. The focus on the female body shifts when the speaker acknowledges the following: what the young divorcé means to do with me The pressure of society coerces the speaker’s lover to deny his sexuality; and, as a result, the speaker’s own self-worth and acceptance of their own identity is diminished. The speaker becomes a subject of shame caught in the web of gendered and sexual politics.

Reed stitches tension, resentment, and grief in “The Fratricide”—a harrowing account of how Black bodies are conglomerate, a startling contrast to how easily identifiable white people are. The poem is damning in its opening lines: “I was coerced into my brother’s murder. Because / I loved him I was made to live for him. Inside him. / As him.” The repetition at the end of the poem creates an uneasy cadence as the speaker cries out: Are we brothers. Aren’t we our brother. This commentary on how Black people are indistinguishable from each other, in life or in death, is layered with suppression, residual anger, and a call for action. The brutalities committed against the Black community are something we continue to witness daily, but Reed refuses to be desensitized by the countless names that have been forged into history because of racially charged violence. “The Fratricide” is a block of text framed around a bolded message: “how can you still not look at his face.” To Reed, it is impossible to ignore these injustices; to turn our backs on these lived realities is inexcusable.

Indecency is a stunning collection lined with unsettling truths as well as fragments of blood and bone. Reed’s craft is undeniable, but one must explicate his poetry like a mortician to fully experience its visceral nature—one must have the ability to uncover the dead without fear. As Reed laments in “About a White City”: “They say there are those / who have never / felt terror.” Indecency is a book that demands to be read on its own terms, and the obscene snapshots Reed strings together will leave you feeling haunted. |

|

Patricia Damocles is the Managing Editor for Jet Fuel Review who is majoring in English Language & Literature with a minor in Creative Writing. She is also a member of Sigma Tau Delta’s Rho Lambda chapter and a Wolny Writing Residency fellow. What she strives to achieve as a JFR editor is to give passionate, aspiring writers a platform to express themselves. As someone who has had the opportunity to be published in a previous issue, she is aware of how empowering it is to have her voice acknowledged in the world of literature. In her free time, she enjoys reading poetry and short stories, and making memories with her friends, family, and cats.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >