- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

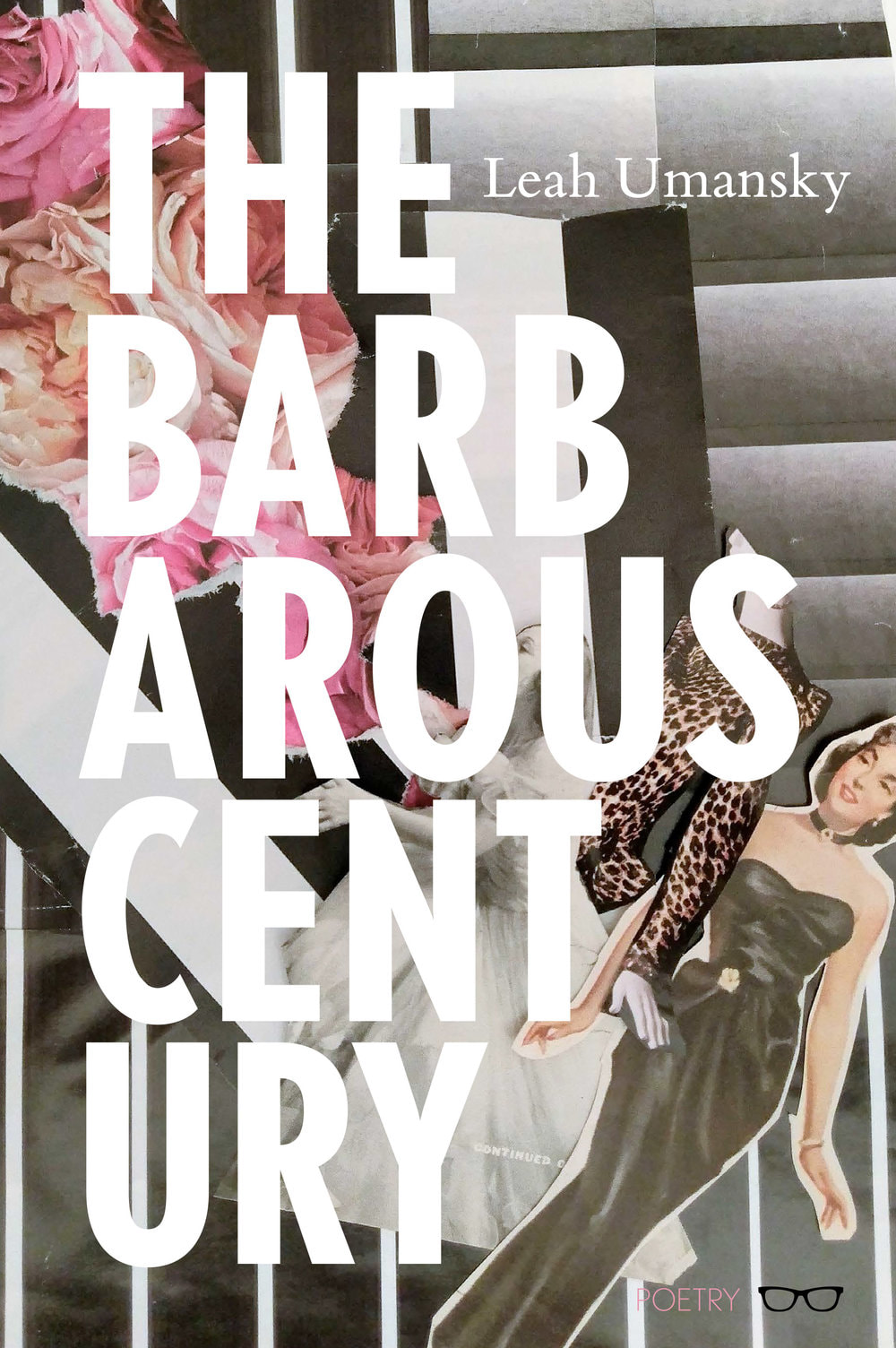

Book Review: The Barbarous Century

|

Review

|

A Review of Leah Umansky's The Barbarous Century by Miguel Soto

Leah Umansky delivers enthralling word-play in her collection of poems The Barbarous Century, while transporting readers between reality and unlikely dimensions. Umansky’s poems critique the psychological manifestation of latent presuppositions of ethics and morality, especially when concerning women. This framework in the social construction of morality, which is already embedded in society’s reality, stretches into the reality of an individuals’ most inventive creations. The Barbarous Century is divided into three sections, “The Lost Just Within Reach,” People Want Their Legends,” and “A History of Sworn Ways,” each illustrating the wants and needs of the speaker(s), who inspect introspectively from predictable as well as imaginative places. In “This Could be Nostalgia” from Umansky’s first section, “The Lost Just Within Reach,” the speaker uses nostalgia as a tool to investigate the shifting between past and present, focusing on the image of “tides” to picture the movement of time. The speaker’s scenic imagery progresses into attentive verbiage, contemplating the intrinsic value in the speaker’s present: We are contemplating the contemporary, The speaker exploits the ambiguity of morphology and diction when denoting the action of “contempting,” to illustrate the existing and continuing disregard for the speaker’s present. The speaker hyphenates the invented word, creating “co-tempting,” attaching new meaning to the unconventional homophones, to regard the present as a subject that evokes attraction to “sin,” or immoral acts. Word-play finds its useful niche, especially in establishing a speculative assessment of contemporary society, or more specifically, society’s “we.” Moreover, in the following stanza, the speaker’s use of “channeling” and “strategize” indicate perceptive qualities of nostalgia, developing into an individual’s manipulation of the past: “we can construct the past.” The conversation between past and present, and the use of nostalgia to achieve this dialogue, demonstrates the structuring of society’s framework, allowing for an introspective response to any individual’s reality.

Continuing into Umansky’s second section “People Want Their Legends,” the reader is taken out of reality, and put into imaginative dimensions, determining a connection between an individual’s creation and the reality of those who watch the creation unfold. Alluding to the characters of HBO’s Game of Thrones, “Cersei” subverts the expectations of reader’s familiarity with the television hit series. For instance, the characterization of Cersei Lannister is often attached to the word “malignant,” but the speaker of “Cersei” wastes no time in saying “she walks for all of us,” undermining the public’s distaste for the fictional character. Furthermore, the speaker not only intends to challenge a reader’s understanding of Cersei Lannister, but humanizes the often-callous Cersei: “she is an emblem of ache.” The word “ache” highlights the trauma the character contains in herself throughout the series. Umansky’s speaker adds, “She is a heroine of hate. A thick-blooded sinner. Warrior. Woman,” proclaiming the admiration for Cersei is in the way she “hates.” Although the speaker recognizes Cersei is motivated by immoral intentions, the speaker still pins the positive connotation of “warrior,” and associates the word “warrior” to “woman.” What the initial two stanzas do in “Cersei,” is question the public’s aversion for the fictional character who do not take into account that Cersei’s actions manifest from layers of latent trauma; and, reason that viewers simply hate Cersei because she is a woman. That is, a woman who defends herself, and refuses to show humility for it. The speaker’s next thirty-six lines alternate between the repetition of statements containing the words “for all the woman […],” and with the response of “shame,” supporting the likeness to Cersei and women outside the imaginative world of Game of Thrones, to show the way creators villainize women for their responses to the world that creates them. Cersei cannot escape the social constructs of the creators who draw her into this fictional landscape, and not even creators can escape the framework of their upbringing in the inventiveness of the fantastical. “Cersei” manifests the notion of a fictional world being subject to the reality of its creators. In the final section of The Barbarous Century, “A History of Sworn Ways,” the speaker(s) sustains transparency, unfolding cryptic reflections through self-examination. In “Bloom,” the speaker admits, “I wouldn’t want to define myself in a single sentence. So / much is already orchestrated.” The lines carry an ambiguity that maintain a load waiting to be unpacked. For instance, the nature of the statement contains an individual’s recognition in their social performance, revealing only what they need to reveal for what the individual deems appropriate for the situation. Divulging feelings is a rarity, and the speaker notes it with a scenario involving a mother and child: “I saw a little boy the other day with his mother. / He smiled up at her screaming with delight, ‘I’m so happy!’/ His mother responded, I’m glad you’re happy.’” The following sentiments contain the residue of envy: “I still think / of the fearlessness he possessed in saying just how he / felt. That innocence. That good despite the world.” The scenario depicts the freedom from social restraint and etiquette that shames people from expressing their sincerity, and it is this child’s freedom from pretense that the speaker finds admirable. From this experience, the speaker is influenced to acknowledge their lack of conviction: “It isn’t easy / to be positive and strong. I’m tired of that directive / dominating me. I’m tired of holding myself up.” The speaker from “Bloom” recognizes a core issue in withholding their true sentiments, which fester, with little to no resolution for relief, acting as a fuel for cynicism and a seal over optimism. Leah Umansky’s The Barbarous Century dissects and reattaches language, playing with the ambiguous construction of words to create a speculative understanding of the human condition’s most pervasive social dilemmas, such as trepidation for the past’s influence on the present, misogyny, and the uncertainty of what truth will arise from self-reflection. The Barbarous Century also critically examines and seeks beyond an individual’s experience and reality, reaching into television and the imaginative, to further establish a comprehension of human afflictions. Umansky succeeds through the condition of being fully transparent in feeling. Leah Umansky’s The Barbarous Century is for the reader who is open to examining their own longing and desires through a variation of tales and poems, ranging from pop-culture, technology, and individual pursuit of lucidity, especially after coming to terms with society’s restraining etiquette toward language, past, gender, and emotion. |

|

Miguel is the Asst. Managing Editor and Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. As an editor, one of his main concerns is giving a space to marginalized voices, centralizing on narratives often ignored. He loves reading radical, unapologetic writers, who explore the emotional and intellectual stresses within political identities and systemic realities. His own writings can be found in OUT / CAST: A Journal of Queer Midwestern Writing and Art, The Rising Phoenix Review, and Rogue Agent. He writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog in Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >