- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

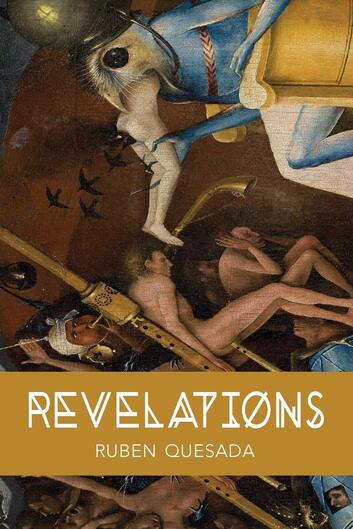

Book Review: Revelations by Ruben Quesada

Ruben Quesada is the author of Next Extinct Mammal and Exiled from the Throne of Night: Selected Translations of Luis Cernuda. His poems and translations have appeared in the Best American Poetry series, American Poetry Review, TriQuarterly, and other anthologies and journals, and he has been awarded fellowships and grants from Vermont Studio Center, Squaw Valley Community of Writers, and Santa Fe Art Institute.

Quesada serves as faculty at The School of the Art Institute where he teaches poetry. Quesada is the founder of the Latinx Writers Caucus, which meets annually at AWP (Association of Writing Programs) and serves to connect and advocate for Latinx and Latin American poets and writers from around the world. |

Review

|

A Review of Ruben Quesada's Revelations

Ruben Quesada’s Revelations is collected within a quartet, each section of poems introduced by a translation of the late Luis Cernuda (1902-1963), a Spanish poet exiled at the start of Spain’s Civil War in 1936. Quesada’s poems meditate from the preceding Cernuda translations to explore the relationship between the human body and language to faith and religiosity. In the opening poem titled “Angels in the Sun,” an existential question is posed in order to mediate the internal struggle with one’s individual faith. The doubt that questions faith is persistent in the subsequent poems, which appear enumerated, as opposed to traditionally titled. “Angels in the Sun” sets up the philosophical inquiry that is explored throughout Revelations in the form of religious awe: Come angles! Come beasts! “Angels in the Sun” points to both reality and otherworldliness to interrogate doubt as well as belief, and also show the communion between holy and unholy in regards to the body’s senses.

For instance, in the prosaic poem enumerated I, the speaker’s first “revelation” points to the individual’s questioning of Christ: Christ was never more than a man nailed to a cross but from him I learned that an entire life fits into a person’s palm like a book of poems like an executioner’s hammer now at thirty five I have learned confession won’t save me Quesada’s poem avoids punctuation altogether, setting the reader into the speaker’s stream-of-consciousness, opening a paradoxical relation between fluid and fragmented. The poem is fluid in that it reveals a narrative, but fragmented in the lineation of how the story is told. Moreover, the presentation of one simile following another allows for a double meaning to one image, all the while giving significance to the following image that appears after the second simile. Specifically, both “like a book of poems” and “like an executioner’s hammer” can be compared to an “entire life fits into a person’s palm,” to imply an “entire life” can be narrated through a book of poems as well as that “entire life” being subject to the dangerous connotation of said “life” being “like an executioner’s hammer.” The lack of punctuation also allows for a second statement to exist for the simile “like an executioner’s hammer,” where the comparison is now situated with “I have learned confession won’t save me.” The poem offers readers their own revelation through the speaker’s shifting change of thought, demonstrating the effect language has on the interpretation of an individual’s beliefs. That said, the imagery quickly strengthens the declaration “Christ was never more than a man nailed to a cross.” Quesada’s form dramatizes the process in reaching truth, and thus offers insight into how belief turns to inquiry and unlocks room for a new belief system founded on the experience of one’s own.

In accordance to the revelatory stream-of-consciousness manifested into a prosaic poem, poem IX offers insight to how the unholy and holy reconcile to offer paradise on earth. In Christian theology, sins of the flesh exist in order to condemn erotism, whereas poem IX subverts condemnation by using pleasure as a means of feeling longing and desire to that joy: you told me about the time in Salt Lake City when you went away to college when you’d spent a night in a sling high on heroin with a line of married Mormon men waiting their turn to be inside you the smell of the fireplace filling your nose is what you remembered most beyond the window mountains blanched with snow The imagery is of drug-use and eroticism, two methods of overpowering the senses in an act of feeling beyond ordinary, arguably beatific. The speaker’s recollection of “high on heroin with a line of married Mormon men” is spoken matter-of-factly, yet matrimony between sacred and profane is read through the piece’s tone, normalizing the sexual act as well as keeping aligned to the thematic doubt over religious veracity within Quesada’s Revelations. The past tense verbs, paired with the serene imagery of “the smell of the fireplace filling your nose” and “mountains blanched with snow,” create the atmosphere of nostalgia. Nostalgia communicates a sense of longing—whether or not the speaker wishes to know and experience what their partner is relaying to them; or, the speaker is mimicking the tone of what their partner tells them. The poem ends on a note of spectacular awe: “above us a hunk of clouds formed grackles crackled above a church lot nothing more was said.” The metaphor visualizes clouds taking the form of blackbirds over a church, signaling a sort of spiritual forewarning. As the poems do not contain incredulity of a higher, divine power, the speaker’s reaction leaves the reader to speculate the significance of ending on a mystic image—what revelation are we now in possession of?

Ruben Quesada’s Revelations explores the truths in paradox, giving sense and dimension to the word “revelation” in order to show the astonishment in obtaining a truth often considered exclusive to divine or supernatural law. Quesada constitutes a newfound belief system from doubt, configures the holy with the unholy, and crafts a beautiful juxtaposition between his narrative poems and Cernuda’s lyricism. Ruben Quesada’s Revelations is an open investigation that allows readers the same privilege—to ask, to answer, and always speculate. |

|

Miguel is a Lewis University alum. He is the Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. He has been published in EFNIKS, Rogue Agent, and others. He also writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog: Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >