- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >

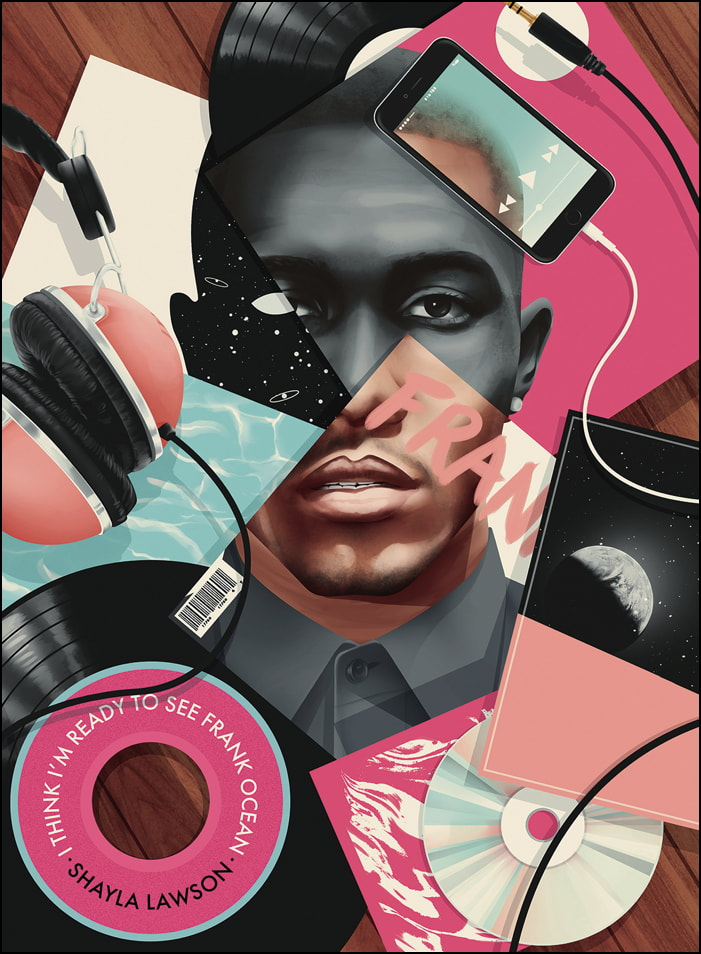

Book Review: I Think I’m Ready to See Frank Ocean

|

Review

|

A Review of Shayla Lawson's I Think I’m Ready to See Frank Ocean by Miguel Soto

Shayla Lawson’s I Think I’m Ready to See Frank Ocean is a complex epic on Frank Ocean’s persona and digital presence, but also a medium for Lawson’s speaker(s) to explore the dynamics within everyday human existence, especially with coming to terms with the reinvention of “self.” Mythologizing Frank Ocean in this process exemplifies the great impact reinvention makes, not only on the celebrity’s status, but for all beings. Lawson’s collection of poetry divides into five sections: “channel(ed), ORANGE,” “ULTRA, nostalgic,” “hello, Lonny Breaux,” “the ocean is ENDLESS,” and “BLOND(e),” speaking to the delivery of an epic narrative. Each poem’s title relates to one of Frank Ocean’s tracks, implementing Ocean’s lyrics in italics to compose the speaker’s own purpose and theme. The mythologizing of Frank Ocean begins with the section “channel(ed) ORANGE,” taking the time to reinvent his and the speaker’s new “self.” For instance, in “Thinkin Bout You,” the speaker begins with “never let an ocean love you,” because “he’ll take / an eternity to do so.” From here, the speaker compares the ocean to Moses asking God, “‘who / should I say comes for the sons / of Israel?,’” and God answers, “‘I SHALL PROVE TO BE / WHAT I SHALL PROVE TO BE’”; then, the speaker interjects with, “which is better than I-Am.” The beginning stanzas show the inception of a persona, using biblical allusions to parallel the effect epic narratives have in formulating and sustaining the creation of idolized figures. The speaker goes further to contemplating this inception: “I wonder / if the ocean will get any older the way / I wonder about humanity,” using the oceanic conceit to illustrate the widespread influence the ocean has in thought and presence. Although the ocean is personifying, the speaker takes time to give it full life through the embodiment of Frank Ocean: […] I wonder when Frank sees The speaker begins to mingle with the idea of Frank Ocean being a reflection of the ocean, and the ocean allowing itself to be an expression of Frank Ocean, proposing to become one. The legend is conceptualizing in “Think Bout You,” and it is the speaker’s capitalization of the conceit that gives the persona’s brand the effect of coming to life like a legend: “The Ocean inside: / every crush, a cymbal crash / every tear heavy as the sea Moses held back / with a staff.” And so, the epic journey for the Frank Ocean persona begins, like the journey Moses took to separate the sea, and because the story is meant to withstand, the speaker warns: “never / let an ocean love you. He will only take forever.”

Under the same section, “channel(ed) ORANGE,” the poem “Pilot Jones” steps away from the analogous allusions from “Thinkin Bout You,” and actualizes the birth of Frank Ocean, personalizing “Pilot Jones” by referring to Ocean’s childhood nickname “Lonny.” The speaker begins by assessing the formative stance a persona can take, saying, “just like a hurricane, Lonny / understands destruction. The force a body swallows to remember itself / mortal.” Although the speaker’s intention is to immortalize Frank Ocean’s persona through the five-part epic narrative, even the person that acts as Frank Ocean understands the limits to mortality, opening a method for the speaker to humanize and humble Frank Ocean’s beginnings: “‘Katarina,’ he utters as her wreckage / bows the floorboards of his college / years, drenches his sneakers in slit.” It is the catastrophic destruction Frank Ocean lives through that allows him to embody the ocean’s fantastic force, and utilize it to become something grand and revitalizing, since “Katrina: / what she don’t drain she baptizes.” “Pilot Jones” means to further the conceptualization of an immortal legend, giving the birth of Frank Ocean the depiction of a ceremonial beginning. In “Pyramids,” also under “channel(ed) ORANGE,” the speaker explores the depths of worship and idolization, taking a step away from the fascination of Frank Ocean. The speaker alludes to Jesus’s death, stating, “The Jesus / I know died on a pole. He / was not a God; he did not want to / be.” Although the stance can be analogous to the icon-branding that people place on celebrities, the speaker determines to keep the situation personal, using some of Ocean’s words to say, “The way / you say my name / in bed. You curse / every god you have / ever met,” questioning the subjectivity in devotion and worship, and even supporting the humanization of past idols. The speaker’s contemplation opens a labyrinth of reflection: […] I wonder why Taking a transcendental approach to viewing the nature of human existence, the speaker relies on herself/himself to step away from the idolization of others and focus more on the “self” through one’s own experiences, thoughts, words, and even though the speaker’s using Ocean’s words as a medium, the formulation of the words remain original to the speaker. The speaker ends with, “working out the pyramid / --scheme: my own toned glory,” reshaping her/his proper image, relative to the reinvention of Frank Ocean from Lonny, showing similarities between celebrity and fan, making the act of creating and living as a persona, or simply a new identity or new “self,” a common, human experience.

Moving into the second section of Lawson’s collection of poems “ULTRA, nostalgic,” the reinvention of “self” becomes vital, not necessarily coveting behind a mask, but embodying a new, empowering identity. “Strawberry Swing” expresses the fear of living in a society that thinks itself post-racial, noticing the erasure of the Black Lives Matter movement, the speaker says, “I have one transcendental / hope that God is erasing our kind / from the dirt,” in hopes of finding a “paradise / in the spaceship of His own / making,” finding a “field of clean dark / faces.” Lawson continues to incorporate Ocean’s lyrics from the song she refers to in the title, pulling words to fill the speaker’s expression of fear, but hope for flight into a new realm. The speaker hinges on themes of love, falling into an uncertainty: “I do not have faith / that all our good will rid these times / of grit,” yet the speaker decides to “make room” and “live / here in what will come,” expressing the danger in thinking optimistically and possibly too far ahead, making the moment a safe-enough outlook. Another poem from “ULTRA, nostalgic,” “Novacane,” Lawson’s speaker reinforces the need to reinvent one’s “self,” culminating the necessity for agency. Following two characters, Alice and Frank, and supplementing the use of Greek allusions, the speaker notices the shift in Alice’s perspective: “She recognizes rape / as a regulatory urge like birth control / or Manifest Destiny,” to “[envisioning] her own agency.” Alice’s revelation allows her to finally speak against her abusive relationship, invoking inspiration from Ocean’s “Novacane” lyrics, saying, “‘It’s super / -human the way I can shut your eyes & still see / everything,’” recognizing the fulfilling ability to validate one’s self, and becoming “someone she wasn’t.” Lawson’s character reinvents herself, approaching an exit from the abusive control her antagonist has over her, and while using the principle medium, each of Lawson’s speakers and characters find a new outlet to act through. In Lawson’s fourth section “the ocean is ENDLESS,” Lawson’s form moves into a lyrical prose, creating an analysis of Frank Ocean’s digital presence, demonstrating the effect his persona emits in the “now.” The fourth segment begins with two major allusions, beginning with Michel Foucault’s “Panopticon,” and the myth of Argus Panoptes, working coherently to illustrate the modern, intellectual prison that is the internet. The speaker says, “so powerful is the mind’s ability to project consequence,” commenting on the confining subjectivity people find themselves adhering to. Argus Panoptes becomes analogous to the billions of eyes that scan over the internet, watching, commenting, and never resting: “so many oculi it was impossible for all of him to sleep at once.” The corresponding allusions affect the era of the imprisoning internet age. It is what the speaker refers to as “our mythology,” arousing the creative invention Lawson is creating, which allows the audience to immerse themselves and find the influence, they too take part in, creating the mythologizing of Frank Ocean: “to image & meme, to snap, tweet, & flutter each instant.” The internet, synonymous with Argus, partakes in building the guise Frank Ocean, but even what is vigilant and always awake, fails: “the all-seeing eye did not foresee this release to the visual album, Endless;” but, even with the copious amount of information that realizes the persona as “imaginary,” “a character,” “a projection—the stage name,” the world that watches Frank Ocean persists on fetishizing the idol—possibly owing the fascination to his origin story, the conceit: “Louisiana native takes on the title of Ocean soon after the ocean erases the homes of his family & loved ones.” Lawson’s speaker creatively dives into new imagery, focusing on killer whales and the infamous exploitation of their ability for entertainment, moving back and forth from the main subject Frank Ocean, but maintaining a metaphorical association. For instance, the speaker’s factual notation notes, “[Killer whales are] victims of a blatant commercial experiment […] plucked from ethnic groups & shipped overseas, exploited for their capacity to perform as powerful, reasonably intelligent, beasts,” relating back to Frank Ocean’s persona, and the plight against commercialism, exploitation of black artists, and corporate branding. The speaker claims, Frank Ocean’s “stillness” is an example of “radical black resistance employed throughout our neo-liberal colonization,” because his “agnostic deployment of patience in the release of his latest album is a critique on expectation; how much ownership we place on any one entity.” Frank Ocean testing his fans proves to go against the current of corporate regularity that drops the latest and newest update in a timely fashion, which schedules masses of people to form a very expected excitement, questioning the ownership of feelings and emotions that come with spontaneity. Frank Ocean determines the release of his own music, working against the regularity of time that is often Capitalized on, proposing that he “[is] waiting on us.” The forth segment of Shayla Lawson’s epic narrative humanizes Frank Ocean, even though the internet’s billions of eyes view his persona vicariously, ignoring the fact that his persona is only one of his multifaceted identities, and by taking this introspective moment to analyze Ocean’s mission and integrity to mean resistance, it is this resistance that fascinates the reader to follow Ocean’s epic journey. Shayla Lawson’s I Think I’m Ready to See Frank Ocean is a magnificent epic narrative on a contemporary artist, envisioning him as a hero-of-sorts. The speaker(s) omnisciently follow Frank Ocean’s persona, not always giving him the full center of attention, but definitely using his persona’s lyrical compositions as a medium to explore personal moments relative to each speaker, giving Frank Ocean a universal grounding in exploring the human experience. Although not physically present in the settings set by the speakers, Frank Ocean’s lyrical compositions, once again, travel, widening the presence and influence of his persona. Shayla Lawson’s project is extremely complex and deeply layered, opening an avenue of creative innovation and possibilities through the creation of a new world through a contemporary figure. I recommend I Think I’m Ready to See Frank Ocean for Frank Ocean fans (obvious reasons); for the creative writer looking to open fresh, creative avenues; for the reader open to exploring the epic narrative in a contemporary, post-modern, free-verse perspective; and, for any reader ready to immerse themselves in Lawson’s deeply socio-political active collection of poems. |

|

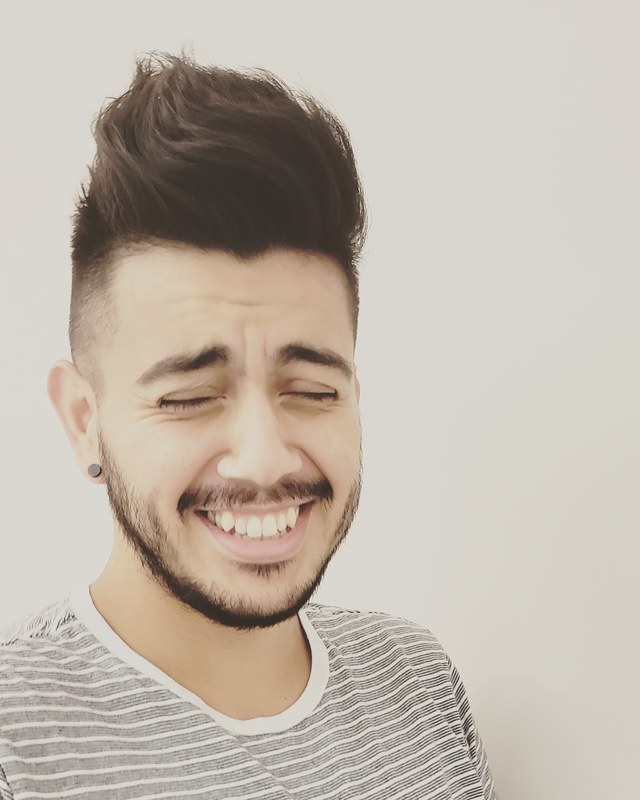

Miguel is the Asst. Managing Editor and Book Review Editor for Jet Fuel Review. As an editor, one of his main concerns is giving a space to marginalized voices, centralizing on narratives often ignored. He loves reading radical, unapologetic writers, who explore the emotional and intellectual stresses within political identities and systemic realities. His own writings can be found in OUT / CAST: A Journal of Queer Midwestern Writing and Art, The Rising Phoenix Review, and Rogue Agent. He writes for the Jet Fuel Review blog in Not Your Binary: A QTPOC Reading Column.

|

- Home

- About

- Submit

- Features

- Interviews

- Book Reviews

- Previous Issues

- Blog

- Contact

-

Issue #25 Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Art Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #25 Poetry Spring 2023

>

- Emma Bolden Spring 2023

- Ronda Piszk Broatch Spring 2023

- M. Cynthia Cheung Spring 2023

- Flower Conroy Spring 2023

- Jill Crammond Spring 2023

- Sandra Crouch Spring 2023

- Satya Dash Spring 2023

- Rita Feinstein Spring 2023

- Dan Fliegel Spring 2023

- Lisa Higgs Spring 2023

- Dennis Hinrichsen Spring 2023

- Mara Jebsen Spring 2023

- Abriana Jetté Spring 2023

- Letitia Jiju Spring 2023

- E.W.I. Johnson Spring 2023

- Ashley Kunsa Spring 2023

- Susanna Lang Spring 2023

- James Fujinami Moore Spring 2023

- Matthew Murrey Spring 2023

- Pablo Otavalo Spring 2023

- Heather Qin Spring 2023

- Wesley Sexton Spring 2023

- Ashish Singh Spring 2023

- Sara Sowers-Wills Spring 2023

- Sydney Vogl Spring 2023

- Elinor Ann Walker Spring 2023

- Andrew Wells Spring 2023

- Erin Wilson Spring 2023

- Marina Hope Wilson Spring 2023

- David Wojciechowski Spring 2023

- Jules Wood Spring 2023

- Ellen Zhang Spring 2023

- BJ Zhou Spring 2023

- Jane Zwart Spring 2023

- Issue #25 Fiction Spring 2023 >

- Issue #25 Nonfiction Spring 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Art Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #26 Poetry Fall 2023

>

- Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo Fall 2023

- Christopher Ankney Fall 2023

- Magdalena Arias Vásquez Fall 2023

- John Peter Beck Fall 2023

- Mihir Bellamkonda Fall 2023

- Benjamin Bellas Fall 2023

- Michael Carson Fall 2023

- Kevin Clark Fall 2023

- Aaron Coleman Fall 2023

- Mark DeCarteret Fall 2023

- Denise Duhamel Fall 2023

- Brandel France de Bravo Fall 2023

- Tina Gross Fall 2023

- Amorak Huey Fall 2023

- James Kimbrell Fall 2023

- Casey Knott Fall 2023

- Stephen Lackaye Fall 2023

- Cynthia Manick Fall 2023

- Savannah McClendon Fall 2023

- John Muellner Fall 2023

- Mollie O’Leary Fall 2023

- Joel Peckham Fall 2023

- Natalia Prusinska Fall 2023

- henry 7. reneau, jr. Fall 2023

- Esther Sadoff Fall 2023

- Hilary Sallick Fall 2023

- Kelly R. Samuels Fall 2023

- Issue #26 Fiction Fall 2023 >

-

Issue #27 Spring 2024

- Issue #27 Art Spring 2024 >

-

Issue #27 Poetry Spring 2024

>

- Terry Belew Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Diamond Forde Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Dustin Brookshire & Caridad Moro-Gronlier Spring 2024 Spring 2024

- Charlie Coleman Spring 2024

- Isabelle Doyle Spring 2024

- Reyzl Grace Spring 2024

- Kelly Gray Spring 2024

- Meredith Herndon Spring 2024

- Mina Khan Spring 2024

- Anoushka Kumar Spring 2024

- Cate Latimer Spring 2024

- BEE LB Spring 2024

- Grace Marie Liu Spring 2024

- Sarah Mills Spring 2024

- Faisal Mohyuddin 2024

- Marcus Myers Spring 2024

- Mike Puican Spring 2024

- Sarah Sorensen Spring 2024

- Lynne Thompson Spring 2024

- Natalie Tombasco Spring 2024

- Alexandra van de Kamp Spring 2024

- Donna Vorreyer Spring 2024

- Fiction #27 Spring 2024 >

- Nonfiction #27 Spring 2024 >